Cirauqui beckoned. The day dawned with perfect weather and a well-made track. We met a French pilgrim from Toulouse, and we all chatted in English. He was a young guy but very interested in people’s stories, and he was really enjoying the Camino. The guy told us he was finishing at Puenta la Reina this year. And that would return next year for the next section. He walked with us until Muruzabal. This is often the way with European pilgrims — it costs little to take a train or bus across the border to resume another section of the Camino. A great way to spend short breaks.

We went in search of a good breakfast at Muruzabal, finding only a few Pasteleries (bakeries) open. But we wanted something more substantial than a cake or bread. So we set off again.

This time we didn’t take the side route to Eunate as we had done previously. It is a fascinating hermitage with alabaster in place of windows. It is an octagonal church surrounded by an ambulatory path made of stones pounded into the ground. The Basque name of Eunate translates as House of 100 doors. This might refer to the arched wall that surrounds the church, or perhaps it is something more mystical.

There is a tradition of walking perhaps three times around to find a secret door. I suspect that door is a spiritual one of the mind — a way into one’s own inner world, perhaps a doorway to our better self. The best explanation is that there are 33 arches around the hermitage. If you walk three times around, that makes 99 doors or arches, and the 100th is the church entrance. The C13th Romanesque church has often been associated with the Knights Templar who typically built octagonal churches to resemble the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Nearby is a graveyard for pilgrims — archeological studies of some of the burials have revealed many with shells or other pilgrim symbols.

One stone stands out covered in mysterious symbols. It took me a while to make the connection between the symbols and the masons’ marks on the church stonework — but the stone records the builders of the church through the marks they made to record the work they did when building the church. This was at a time when builders didn’t typically sign their work, so they have been recorded for posterity known only by their mark.

The carved pillars have early Gothic features. Inside, the arches in the cupola cross in a manner similar to Islamic Cordoban or Templar architecture. The masons’ marks suggest around 9 masons worked on the church. The design works well, as the acoustics inside are wonderful. You can easily imagine the blended harmonies of Gregorian plainsong or strains of Dum Pater Familias from the Codex Calixtinus reverberating through the clouds of incense.

But this time we knew it would be a longer day as we had been unable to find accommodation in Puente la Reina, so we would be traveling a little further. Near where the path to Eunate rejoins the Camino is the town of Obanos, just before Puenta la Reina.

This medieval town is at the conjunction of two Camino routes — the one from Roncesvalles, the other where the Arlesian route that crosses at the Somport Pass joins the Camino Frances. So it has several churches and pilgrim hospices. By the church, I read a signboard that tells of a local legend recorded in a C14th Mystery Play.

In the play, Duke Guillermo (William) of Aquitaine made a pilgrimage to Santiago with his sister Felicia. As they were returning, she announced that she could not return home to Acquitaine, but would instead become a hermit in northern Navarra. The Duke had anger management issues and tried to force her to return with him to court. In his rage, he ended up killing her. At that, he realised the enormity of what he had done. So he resolved to return to Santiago as a penitent. On his return journey, he decided to stop in Obanos and establish a hermitage at nearby Arnotegui, building a chapel to continue his sister’s mission.

To some extent, the Duke in this example applied a form of restorative justice to himself. While retributive justice might have demanded his life. He instead chose perhaps the more difficult path of living with the consequences of his actions. If he had been a Stoic, perhaps he would have acknowledged his anger, before stepping back from it to identify the source, and he might have realised that his sister’s choice was not in his power to control. He perhaps could have controlled his reaction to his sister’s decision, but chose not to. And in that rash moment changed the course of both of their lives forever.

The Stoics might have considered that in the grand scheme of things, his sister’s intentions were ultimately achieved for the good of society. Of course, had he been a Stoic he likely would not have taken his sister’s life. He would have returned to court alone, and his sister would have lived out her days as a hermit helping other travelers as they passed by.

As a morality play, this story certainly has lessons aimed at being more stoic and acting more from the head than the heart. But sometimes it takes a dramatic life-or-death story to remind us to be ethical in our dealings with others. A lot of novels and movies base themselves on such drama. As we drank our tea we talked about how people need to have drama in their lives — something larger than life — but this can also lead to unnecessary drama in social media as well! It’s all too easy to jump to rash judgement on the basis of a headline or a soundbite.

By now I was really starting to crave a second breakfast of bacon and eggs. And I would have to wait a further 2.5kms until Puente la Reina to find it. So Sharon and I took up our poles and headed out on the track.

There were wildflowers in profusion alongside the track and in places the hedgerows almost formed a tunnel that provided welcome shade and a picturesque frame for the track.

Puenta la Reina, or the Queen’s Bridge is named for Queen Doña Mayor, wife of King Sancho III. The bridge was built in the C11th spanning 360 feet and served as both a safe crossing of the river, but also a defence, as it once had three towers — you can see the remains of one of the towers which now forms part of the visitor’s centre. There’s also a small museum attached to the tourist office which is well worth a visit. The Templars built a hospice near the entrance to the town.

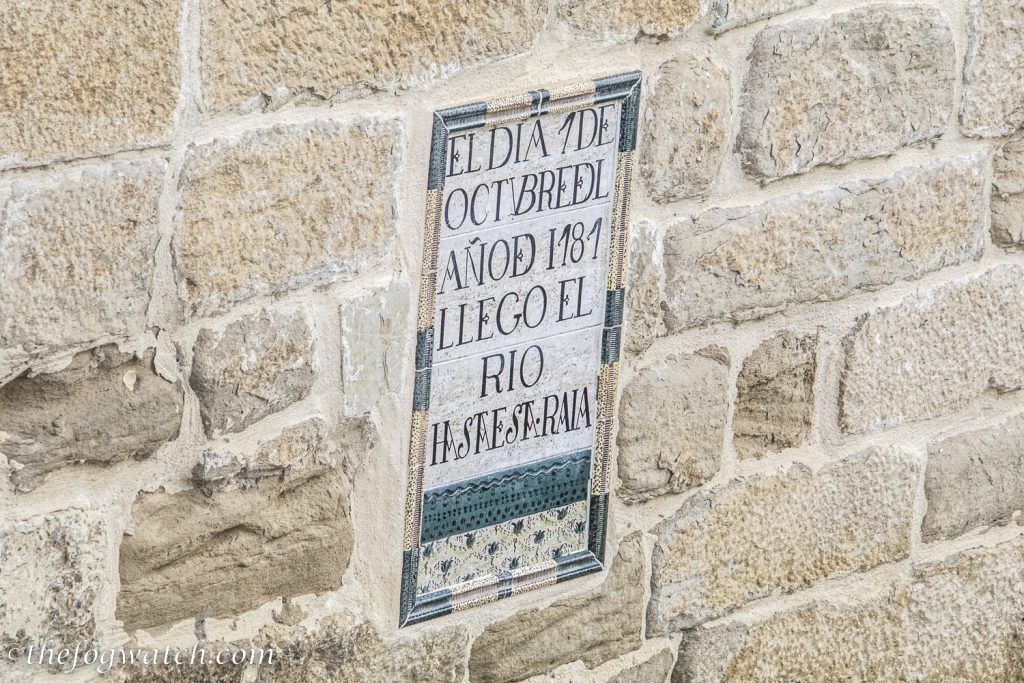

The river can be quite treacherous, as it swells substantially with the Spring meltwater from the snows. A plaque next to the bridge shows the water level in 1181 when the river reached almost to the level of the bridge. The holes above the piers reduced weight in the structure, while providing a way to reduce the pressure against the bridge. Some claim that the bridge has Roman foundations. But there’s actually no evidence of a Roman road at either end of the bridge. So it seems that the bridge and the town emerged from the early medieval period —at least in part to provide rest and shelter for the pilgrims. In the end, the bridge appears to have been built due to the level of banditry and extortionate ferry tolls levvied on the pilgrims.

The bacon and eggs didn’t disappoint, and sustained us well for the rest of our day’s walk.

We set off again and soon we found the small hamlet of Maneru, before more countryside enveloped us. The path curved gently, following the contour of the hill. And it soon gave us a vista of Cirauqui in the distance, looking like a medieval map of a town, with the buildings rising in layers, ultimately surmounted by the church (Iglesia de San Román) built around 1200 AD — always on the highest ground.

This has to be one of the most picturesque approaches to a town on the whole Camino. Wildflowers and market gardens led the way. All the while the village stood out in orange stone among the green pastures, beneath an azure sky. I pictured a scene from the film Name of the Rose. A pilgrim monk walked with his novice, both in brown robes in the C14th, perhaps making this same road. A town has stood on this site since Roman times, as evidenced in recent archeological excavations.

We entered the town, winding our way through narrow medieval streets climbing like the Camino marker said, towards heaven. I wondered if heaven had so many hills. At the steepest part, we entered a small plaza and found our accommodation at Albergue Maralotx. We had booked the private room, upstairs, and found a view over the town. We showered and washed our clothes — part of the daily routine — and found washing lines on the balcony.

Dinner in Cirauqui was wonderful. The place was busy and there had been a continuous stream of pilgrims undiminishing throughout the day. This is a busy year! The waitress was rushed off her feet. I used my best Duolingo Spanish to order. And at the end of the meal I did the pilgrim thing and took my plates back to the counter so she didn’t need to make an extra trip. I told her she was doing a great job and that we appreciate her work.

As she brought our pots of tea, she turned and thanked me profusely. She was genuinely moved that someone had noticed her work and expressed appreciation. For me it was just part of the journey to notice and to show appreciation and gratitude. We often don’t realise that a small kindness can really make someone’s day. There were many times on the Camino that I was brought to tears by someone showing me a small kindness when I needed it.

And so to sleep.