Bound for Sansol, we left Villamayor de Monjardin before sunrise, taking a farewell photo of the church as we headed down the hill and out into the valley.

The kites soared over the hills as we headed out of the town.

Looking back into the ripening dawn we could see the castle and the commanding view it had over the region. It had been an important strategic stronghold since Roman times, and then for the Moors and finally for the Christians that reconquered the region.

As we descended into the valley, our path ahead lay crisscrossed with a brilliant patchwork of yellow canola fields and waving barley, shimmering in the breeze like water on a lake.

At length, we came to the great dog-leg where the path skirts around the farmland. We followed it leftward to the end of the paddock, then a right-angle turn to the right. We were keen to cover ground in the morning as it would be 11.5 km before the next village — Los Arcos.

Looking out over the expanse of green and gold, in the distance, perched among the rocky crags stands an ancient monastery or hermitage. The last time we passed this way, the clouds were rolling over the top of the mountains and down into the valley — a surreal scene reminiscent of an apocalyptic movie.

But today, it is a perfect Spring day with an almost cloudless sky. Purple sprays of wildflowers lit up the path.

Eventually, we came across the market gardens and immense half-collapsed hay stacks — The scale of the haystack had me concerned about spontaneous combustion — it would certainly have been an issue if this was in Australia.

Los Arcos

And suddenly, we were walking into Los Arcos.

The town has existed since Roman times and five Roman tombs were found at a small Ermita (hermitage) on the outskirts of the town. At that time it was known as Curnonium, and was mentioned by Ptolemy in his Geographica Iberia.

Conquered by the Moors, the forces of Sancho Garcia I retook it at the battle of Valdejunquera.

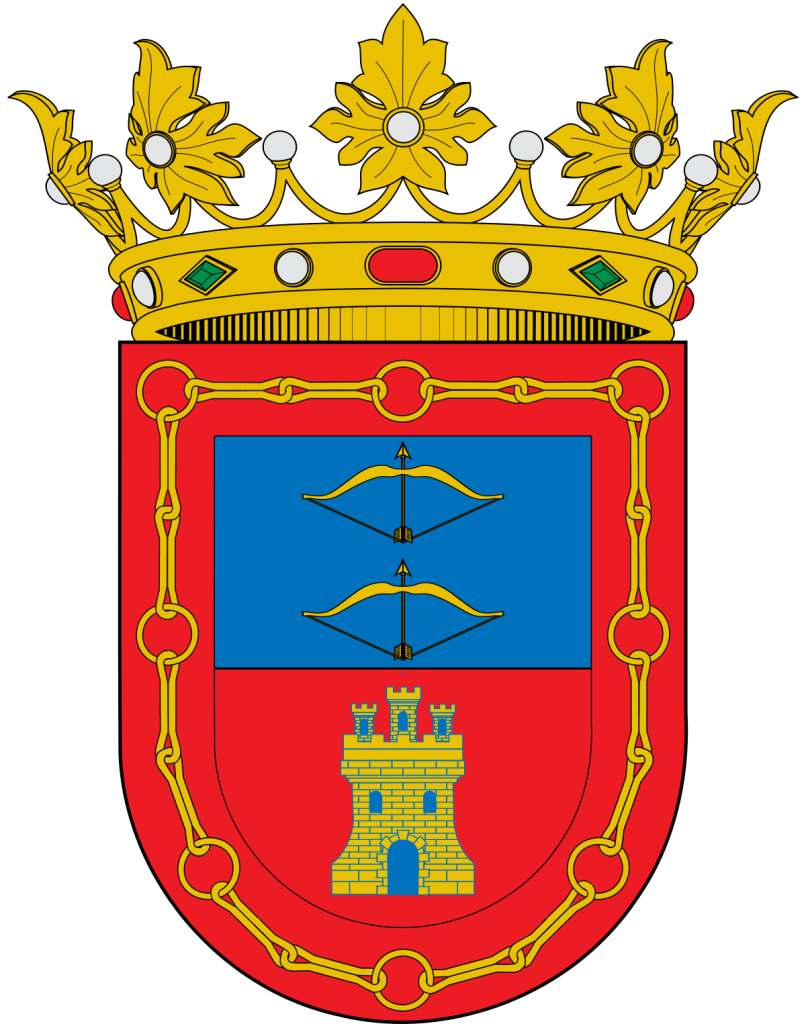

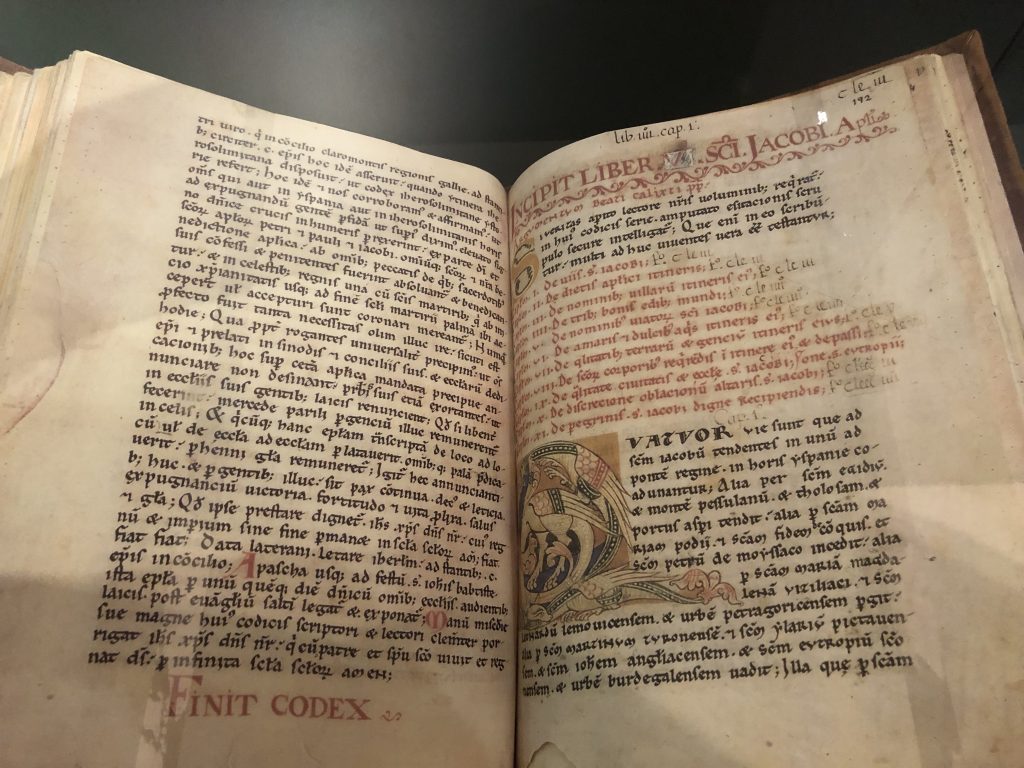

In Codex Calixtinus it is mentioned as Urancia — now called Los Arcos — and its name came about after the battle of Valdegón in 1067CE. The battle was between the Kings of Navarra, Aragon, and Castilla. It was won by the army of Navarese King Sancho el de Peñalén. He then awarded the town a new coat of arms, honouring the archers by including bows and arrows on the Heraldic symbol. From then on the town was known as the town of the archers, or los Arcos.

In 1175 CE the King awarded Los Arcos its own warrant to hold regular markets, and from there the town prospered. Such a warrant permitted towns to earn revenue in their own right, and given its location next to the border with Castille, it would prosper from cross-border trade as well as trade from the local population. Its location close to the border also gave the castle strategic importance in the region. It changed hands between the two kingdoms several times, before finally being settled as a Navarran town. But it retained a free-trade agreement across the border with Castille. By now we were really feeling like breakfast, and looking forward to perhaps some nice tortilla patata and a good strong tea or cafe con leche.

Into the Square

The main street is like a theatre set, with rows of buildings — actually just their facades — as there is nothing behind the walls. Vacant. It is a trace of history but without substance to fill out the story. Derelict, but with a promise of renewal. It is a place caught in a hiatus between past and future — a shell, a golem of history.

We headed for the main square where tables and chairs sat beneath umbrellas. We found a bar and I ordered tortilla patata, tea, and a refill of our water bottles. The Spanish youth behind the counter showed little interest — as though I had interrupted his morning. He clattered around ineffectually, tossing the tortilla casually into the microwave and pouring two metal teapots of hot-ish water, before eventually deciding to include a couple of tea bags beside the cups.

Outside, in the square, a young French pilgrim sat nearby, and we all started talking. She joined us at the table. An Anaesthetist by trade, she was somewhat burned out by the intensity of working as a front-line medical worker during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in an under-vaccinated country.

A philosophical moment

We talked about philosophy and the Camino. We discussed why we walk the Camino, And the Franciscan theology in which God is perhaps another word for the Universe, or Nature (sounds like the Stoic philosophers). From there, we talked about ethics and how the Camino provides a compass to steer us back towards our better selves. And, importantly, how to take the Camino home afterwards.

I took a bite of my tortilla and nearly gagged. The egg in it was bad, and I suggested to Sharon that we shouldn’t eat it. We still had some way to go and didn’t want to get sick. So we were left with tea, bread, and water. Victoria — the French pilgrim — expressed concern. I said: “It’s only life”. And then recalled that Epicurus had once said that the most important ingredient in any meal is good company. He said: “We should look for someone with whom to eat and drink, before looking for something to eat and drink.” For Epicurus, the food may be as simple as bread and water — but when eaten in good company, it is as good as a banquet.

I looked up at Victoria and smiled, saying: “So, we have a banquet”. At that, she teared up and gave us both a big hug. Epicurus’ point was that food can fill the body, but friends will satisfy the soul. She then walked on as she had much further to go than we did. Perhaps also, she had much to think about and digest on her journey — and not just the food!

Codex Calixtinus

The Codex Calixtinus was not encouraging about the waters in Los Arcos, finding it unhealthy:

“Through the town called Los Arcos runs very unhealthy water. And beyond Los Arcos, next to the first hospital, that is, between Los Arcos and the hospital itself, runs a deadly watercourse for the animals and men that drink from its water.” The latter part possibly refers to Sansol. Fortunately for us, the local council provides filtered and treated town water in both Los Arcos and Sansol. And today, it is fine to drink. The fountains too are safe all along the Camino.

The church was closed as we headed out beneath the arch into the rolling farmland. The poppies mixed with daisies on the edge of the canola fields. And we could see our destination in the distance in much the same way as medieval pilgrims would have.

On to Sansol

At length, we approached the medieval village of Sansol. And the venue for our accommodation that evening at the Hostal San Andres which surmounts the path into the town. Sansol was named for a Christian martyr, San Zoilo. He was martyred in Cordoba under the rule of Diocletian in 304 CE. His relics are in the Benedictine monastery of San Zoilo de Carrion at Carrion de los Condes on the Meseta. His name was mentioned in St Jerome’s Martyrologium (Martyrologium Hieronymianum) compiled around 392CE from several sources in Rome, Africa, and Greece.

Sansol once had a hostel and chapel dedicated to Santa Maria de Melgar mentioned in the Codex Calixtinus. It belonged to the Hospitallers of St John — the successors to the Knights Templar. The Baroque C18th church of San Zoilo has a dome painted with the Ascension of Christ.

From kites soaring above the castle, to an Epicurean discussion over bread and water in a town named for the archers that ensured victory over rival claimants, and on to a village named for a saint martyred by the Romans in Cordoba, it was quite a day. We were ready for a rest.

I took a photo from our window overlooking the Camino path into Sansol. It was already getting dark. And we headed downstairs to the bar for dinner and wine. And so to sleep.