In Belorado, we had a comfortable private room in a hostel, and we’d had a good dinner of salad and chicken followed by dessert. But I passed a restless night with foot cramps. Rising early, we packed quietly and headed out on the way to Villafranca Montes de Oca.

Belorado itself dates back to Roman times. It was given a major boost in 1116 CE, when Alfonso I el Batallador granted the town a Fair, or market, known as a Fuero. Like other market towns, its population was diverse. The town was divided into separate neighbourhoods for the four major ethnic groups, the local Christian Castillians, the foreign French Christians, the Jews, and the Moslems — each neighbourhood had its own traditions and judges.

Alfonso I also granted equal rights to Christians and Jews, and as in many regional centres, instituted some curious regulations and laws. For example, Alfonso’s laws exempted Belorado’s Jews and Moslems from taxes for most of the Middle Ages — instead giving them responsibility for maintaining the upkeep of two of the town’s defensive towers. And Belorado’s Jews had an additional arrangement to provide two men to sweep the streets every Thursday, in exchange for being allowed to pasture their cattle on city lands and collect firewood from the municipal forests. I found it interesting how diverse the medieval populations were, and how they accommodated to each other, even as former adversaries.

As we found the way markers, we soon saw a sign that told us to walk 100 steps and then turn around. We did so, and we were rewarded with a pair of amazing murals, an abuela (grandmother), and a young girl.

The medieval bridge beckoned us onward into the open countryside.

We crossed the bridge over the river Tirón, and looking down into the parkland below, saw lights suspended like droplets.

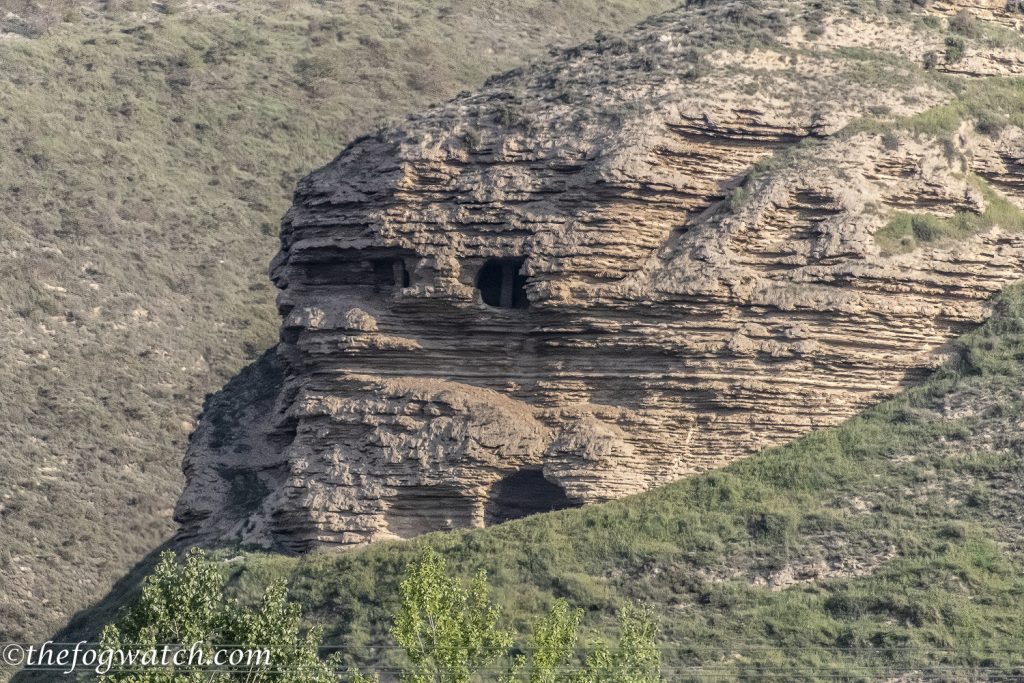

We walked for some time until we could see the hermit caves of Tosantos in the distance.

At some point, we approached a pilgrim resting in the shade of a tree and asked if he was okay. He nodded. I asked where he was from and at some length and with clear difficulty he slowly sounded out ‘Port-u-gal’. We told him we were from Australia. At first, I thought he was struggling with the translation of our question, so we wished him a friendly ‘Buen Camino!’ and walked on.

We talked about the translation thing, but something bothered me. And I replayed our interaction over in my head, and then said ‘I don’t think it’s a translation problem, but a severe speech impediment’. I sensed he had understood what we said, but struggled with the mechanics of speech.

We stopped in Tosantos for a tea, more like a cappa-tea-no — tea made like a cappuccino, with frothy milk! We chatted for quite a while with another pilgrim couple, before heading back out on the road.

You can see the Tosantos hermitage chapel (Ermita de Nuestra Señora de la Peña) cut into the cliff above the town. An extraordinary sight. There is a legend that says that in 712 CE, the Christians hid an image of the child Jesus under a bell in this cave to protect it from the advancing Moors. The current image is actually from the C12th, but legends are like that. It is kept in the Ermita during the winter, and the summer in the church of San Esteban in Tosantos village.

After our rest stop, and with water refilled, we followed the arrows out of the town. The path was long and straight and close to a main road. We saw a pilgrim some distance ahead walking with shuffling steps and heavily reliant on his trekking poles. And soon we caught up with him. He was the pilgrim we had met earlier.

I tried my basic Spanish and learned that his name was David. His responses were slow and halting. I asked if he had a problem with speaking. He nodded, and pointed to his head saying he was ‘enferma’. I nodded. Then I asked if he had hurt his head in an accident, and again he nodded. As we walked together and continued our slow conversation, we learned that he had been a keen cyclist and two years ago he had a bad accident, leaving him with brain damage that affected his speech production and mobility.

His son was a doctor and was helping him with his recovery. David’s speech was slow and slurred, but it was clear that the intelligence behind his eyes was undiminished. He understood Spanish and English well. And, as we were not in a hurry, we talked for quite some time, gaining understanding as we tuned in to his speech patterns. Sharon said it must be very frustrating for him, and he stopped with tears in his eyes and hugged us. He called us his Camino angels. Communication is so important to our well-being.

Few people had taken the time to try to understand him. So it must have been a very lonely Camino so far. We talked some more and laughed and joked with him. He clearly understood what we were saying and he laughed with us. The more he relaxed with us, the more he found it easier to talk, and we discussed the differences we had noticed as Australians in Spain, and he talked about Portugal and his cycling trips. He had previously cycled the Portuguese Camino. And today he was walking the Camino Frances to help with his recovery process. He has a long journey ahead, but hopefully, we made part of his journey a little easier. I raise a glass to him as his journey has required him to overcome so much. I really hope he made it to Santiago okay. He has true courage.

We stopped for a proper lunch at Villambistia — bacon and eggs, fresh squeezed orange juice from a Zuma machine, and tea.

In the cafe, we spoke with Sheila from Ireland — she was an infection-control nurse and had been affected by working very long hours and had seen quite traumatic cases during the height of Covid. She was taking a well-earned break having been a front-line worker throughout the pandemic — a true hero.

We took another rest stop at Espinosa del Camino, where we refilled our water bottles on the other side, not the one with the horse trough!

As we headed out, we passed an old Camino marker while descending through rolling farmlands alongside a very small ruin. Our destination for the night was in sight — a welcome view!

We descended towards Villafranca Montes de Oca, and came upon what appeared to be a small gatehouse or toll-house. Known as San Felices de Oca, it is all that remains of a major Mozarabic monastery begun early in the C9th. A Roman villa once stood here, providing the foundations for the monastery. The early counts of Castilla used this once-grand building. And Diego Porcelos, who led the reconquest of Burgos, was buried here. A small find, but with a mighty history!

We crossed a creek supposedly inhabited by otters (we didn’t see any). Then, we climbed the final rise and found our accommodation at San Anton Abad opposite the church. Our accommodation was full of antiques and quite luxurious — we were in the hotel section rather than the albergue.

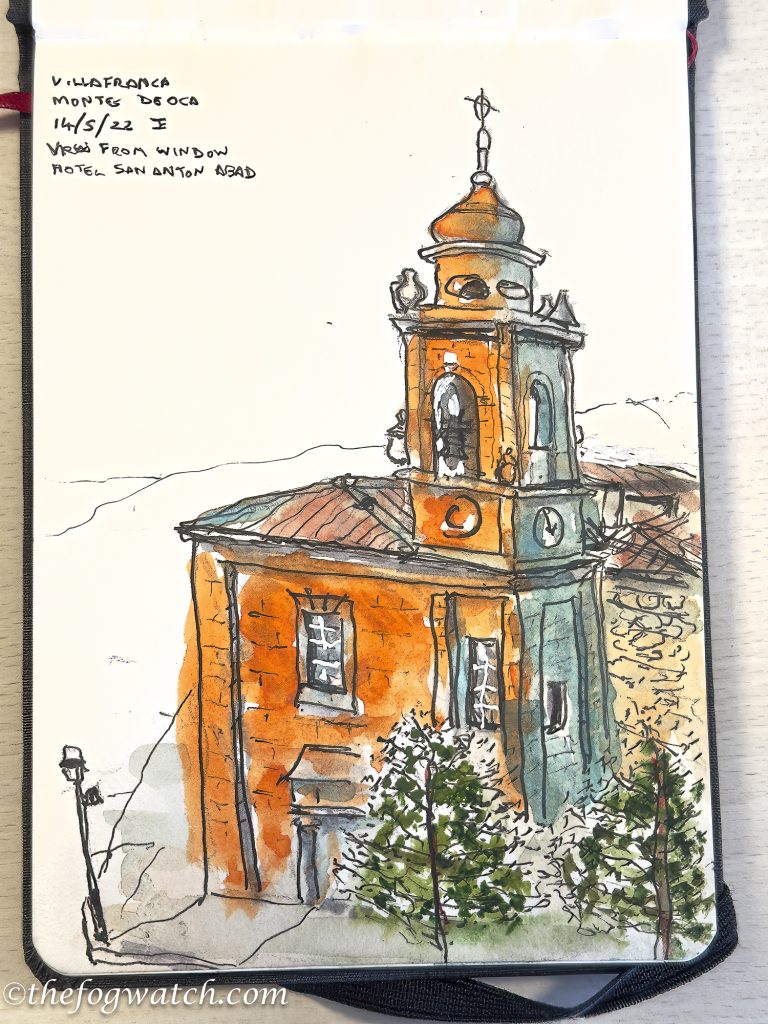

And we had a good view of the church, which I sketched quickly. It was a great exercise to focus my observation skills for Burgos Cathedral.

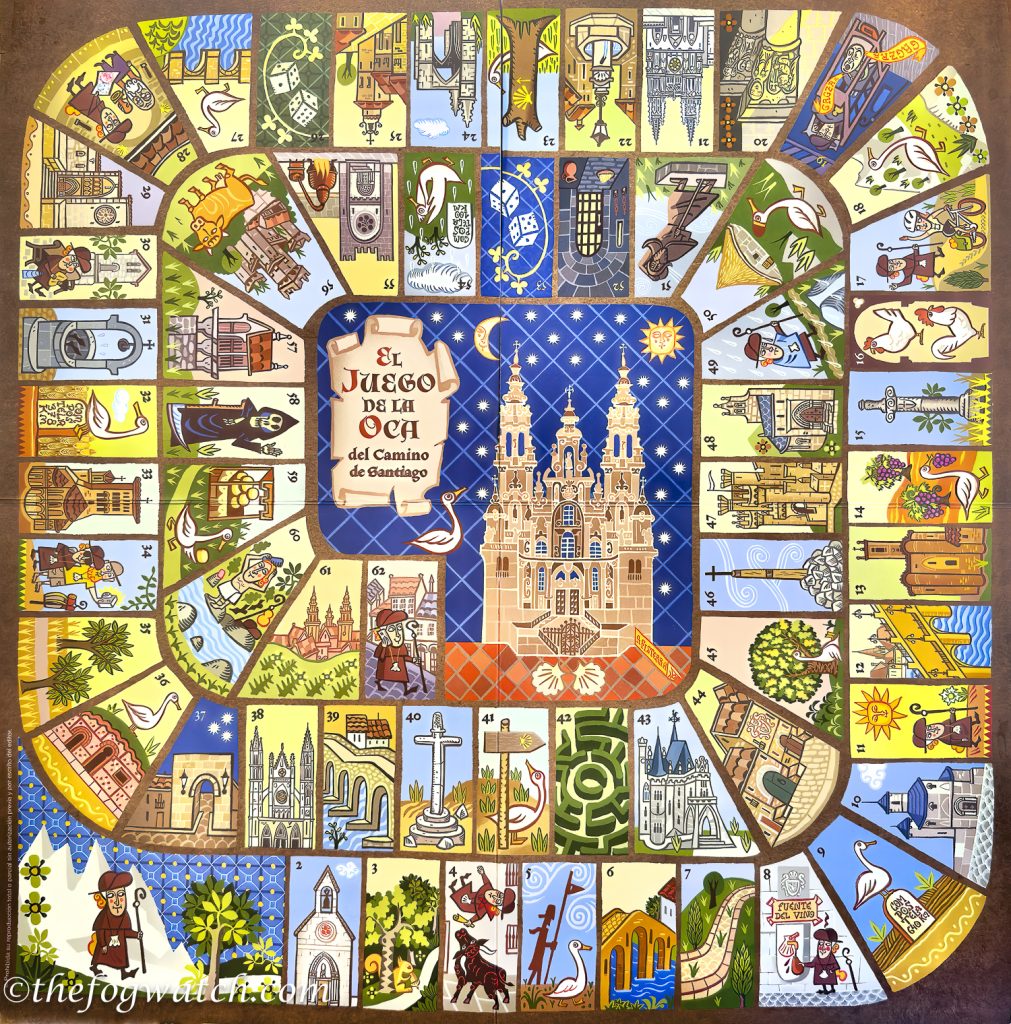

Villfranca Montés de Oca — which roughly translates as ‘The Frankish Town of Goose Hill’ — has a chapel called Our Lady of the Goose. The goose reference ties it strongly to the traditional Game of the Goose. Some say it is a sacred Templar map of the Camino de Santiago. The game is marked with significant places. A labyrinth may warn of a confusing trail. Or it could warn you to be wary of losing your moral compass. The Camino is an inward as well as outward journey.

Other symbols like the well, may indicate the availability of water. But if you fell in, it could warn against being distracted or dissuaded from continuing your journey, so you lose a turn. There are places of welcome, with bridges such as Puenta La Reina, or Hospital de Orbigo. Significant churches can provide sanctuary from the arduous road. In medieval times, literacy rates were low, and a pictorial map would help pilgrims to remember the Way. The game can work like a guide using tokens as avatars to enhance your memory. Often pilgrims didn’t carry the game on a piece of paper or parchment or wood as we might today. Instead, pilgrims would draw it out from memory on the ground when it was time to play the game.

In medieval times, people would navigate by the migratory path of the geese during daytime, and by the stars at night. And since geese migrate from East to West, they were a fairly reliable guide for the pilgrims. The Romans used them to guard people’s homes. The Celts viewed them as symbols of wisdom. In addition, their footprints were similar to the scallop shell, bringing all paths to a single point.

Some churches on the Camino have goose symbols or goose feet incorporated into their decoration. The Templars considered such places to be significant.

The Templars were among the early bankers on the Camino. So a goose foot symbol might well have acted like a medieval ATM sign, and a sign of protection.

The death sign near the end is also a symbol of rebirth. It is like the Cruz de Ferro where pilgrims leave their past selves behind. Here, they are symbolically reborn to take what they have learned from the pilgrimage back into their daily lives. The game is in a spiral, like a journey to the centre, followed by the return home to our outward lives.

From wall murals, past a troglodyte hermitage, to thoughts about communication and the importance of language, our journey today took us to a town with a special relationship to the Templar Game of the Goose.

Hello Jerry

In France it is “Le Jeu de l’Oie”. The village next to ours is called …L’Oie. There is a crossroads where the present St-Malo to Bordeaux road crosses the Angers to Atlantic coast road. I gather that the latter was an ancient salt road in Roman times.

What a continuing pleasure to read your stories.

We are investigating the ancient Camino route btwn Nantes and La Rochelle at present with our neighbours; the hamlet at the top of the hill here is called L’Hopiteau. ..

Any plans to publish your stories in printed form?

Thank-you once again for your inroads and your insights.

Always a welcome for you here.

Alan & Shirley

Salut Alan and Shirley! — thank you for your lovely comment — and yes the game of the Goose can be found throughout Europe in various forms, including as a form of Snakes and Ladders. I would love to hear more about the Camino route between Nantes and La Rochelle. I have visited Nantes a few years ago — a fascinating place with a wonderful history. I was recently interviewed by Dan Mullins for his Camino Podcast series, and he asked me the same thing. As I continue to research the history and philosophy behind the Camino I find I have a lot of material suitable for print, and at some point I think these blog posts will form a framework for a book in due course. In Medieval times it was common for pilgrims to travel a circuitous route through France, visiting various Saints relics along the way. Such sites included Tours, Chartres, Arles. and many others. I hope we can meet up some time to exchange ideas 🙂 Cheers – Jerry