To get to Santo Domingo de la Calzada, we have 21 kms ahead of us so it’s time for an early start. Out the door at 06.30 AM and straight into a climb as we wound past the cave monastery and onward through a rock cutting.

A bright yellow arrow painted on the road with the stylised shell motif greeted us as we left Nájera. This gentle reminder of our purpose lifted our spirits immediately.

The fields of barley waved like a green lake rippling in the wind. Cadmium-yellow stripes of canola punctuated the verdant green — a refreshing sight in the early morning light.

We continued onward towards Azofra, which presented from a distance like a medieval map laid out in layers looking down on the valley, topped of course, by a church. The view was a little interrupted by the industrial warehouses on the outskirts of the town.

Over breakfast of tortilla patata and cafe con leche, we chatted with a Danish woman who asked how we had managed our 42 years together. We laughed and talked about how we set out to make each other laugh at least once every day, and that we communicate well, and leave space for each to grow in their own way — that way there’s always something new to discover about each other.

Suitably refreshed and back on the road, a French couple walked a little with us, and on hearing we were Australians, welcomed us to Europe. He was from Strasbourg, and she was from Nantes — they were surprised we had visited Nantes on a previous trip and how we enjoyed the gardens there and of course the famous Machines de l’Isle — giant puppets created in the workshops of a former naval shipyard. Being younger and fitter than us, they left us after a time to walk on ahead — it’s perfectly fine as it’s important to walk at the pace you are comfortable with.

The road is very straight and long and bears many hallmarks of its Roman origins. Green barley fields rippled in the wind on either side.

Of course, you are never alone for long on the Camino, and soon we had caught up with a woman from California who had a truly remarkable story — perhaps one of the true miracles of the Camino. A year ago she was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer. She became very sick and was under heavy chemotherapy but it looked fairly hopeless. And with her immune system compromised, she came down with pneumonia. Her husband watched over her in the hospital. Soon, she passed into a coma and a priest gave her the last rites.

No one expected her to survive until morning. Her husband prayed for a miracle and talked to her about how she couldn’t die now as she had always wanted to walk the Camino, and if she died she would not be able to fulfill her biggest ambition to walk this pilgrimage to Santiago.

As dawn broke she woke up. Her cancer went into complete remission to the astonishment of the medical staff. Within a couple of weeks, she was discharged from the hospital with no detectable sign of the cancer. She and her husband took it as a sign for her to walk the Camino, and here she was, walking in gratitude and well on her way to Santiago. We both had tears and she gave us a big hug and we walked on together talking about our respective countries and things we had observed on the Camino.

We came to Cirueña and parted ways as we stopped for coffee and second breakfast, well, cake anyhow because life is short, so dessert must come first — and we thought about the amazing story of fortitude and strength this woman had shown us.

As we left Cirueña, we saw three Franciscan monks dressed in their brown habits with white ropes as a belt, with three knots denoting the three vows they took to join the order (poverty, chastity, and obedience). The monks had equipped themselves well with backpacks and trekking poles, for walking the Camino — it was somehow reassuring that the church still places value on the pilgrimage.

The terrain was good and as we crested a hill we saw a flat steel sculpture depicting Santo Domingo beneath a bridge pillar — the sculpture is remarkable as it looks three-dimensional yet is a flat plate. It’s very well designed by José Ramon Rodriguez. In the C11th St Domingo built a bridge over the River Oja to enable pilgrims to cross in safety. As we entered the town we encountered a metal sculpture of a stylised pilgrim, next to the entrance to the Monasterio de Nuestra Señora de la Anunciación.

According to the signboard, the Bishop of Calahorra y La Calzada founded the monastery in 1610. The chapel was built by Matias de Astiazo, and today the old Chaplain’s house is used as a pilgrim hostel.

We headed further on into the town to find our accommodation in the town square next to the cathedral.

The town is Santo Domingo de la Calzada, or St Dominic of the Causeway. Domingo Garcia used his engineering skills to build bridges and roads to help pilgrims on their way to Santiago. He was born in 1019, the son of a peasant. He tried to join the Benedictine order twice, but the order refused him both times. Domingo then went to live as a hermit in the nearby forest until 1039.

At that point, he began working with Gregor, Bishop of Ostia. The Archbishop sent Gregor to the region to combat a plague of locusts. Gregor ordained Domingo as a priest, and together they built a wooden bridge over the river Oja. After Gregor died in 1044, Domingo arranged to clear the area of trees, developed agricultural land. And they built a road or causeway to replace the traditional Roman road between Logroño and Burgos. In time, Domingo’s road became the main route between Nájera and Redecilla del Camino.

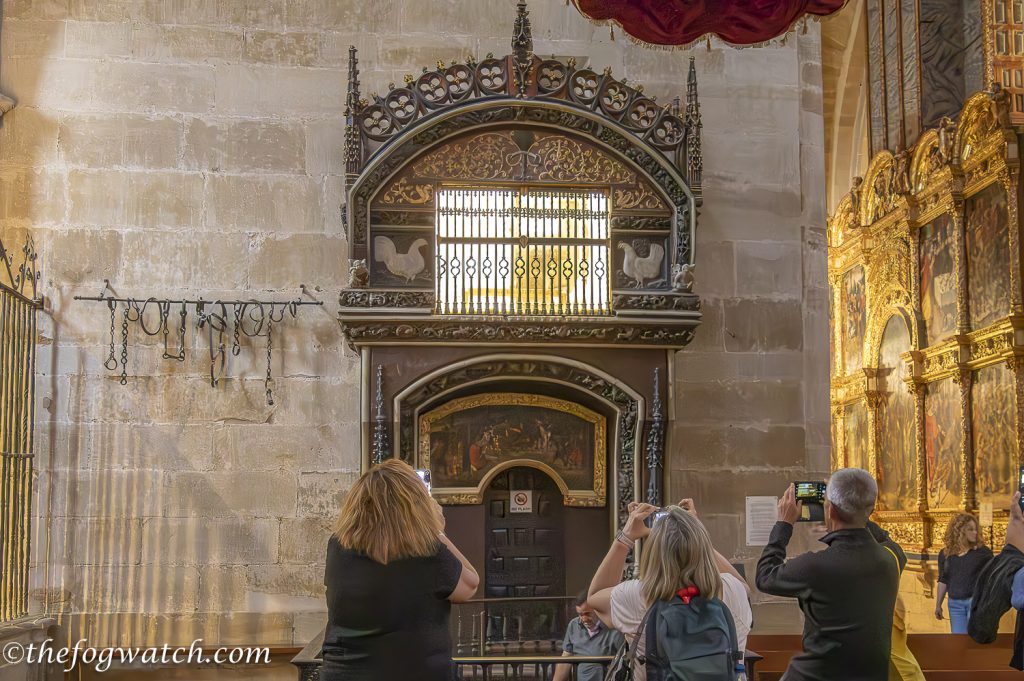

Juan de Ortega joined Santo Domingo in his work and together they replaced the wooden bridge with one of stone. They also built a pilgrim’s hospice built on the site of what became the Parador. The hermitage in time gave rise to the town that bears St Domingo’s name. Several miracles were attributed to Santo Domingo, but the best known is the legend that gave rise to the chickens in the church. So now, yes, healthy chooks (a rooster and a hen) strut around a large stall inside the church. If you believe the stories, the chickens bring good luck if they crow during mass. The legend goes like this:

In the C14th, an 18 year old named Hugonell, together with his parents, were on pilgrimage to Santiago, from Xanten. A barmaid at the local inn took a fancy to Hugonell, but he rejected her advances. So she hid a silver cup in his bag, and then informed the magistrate. Hugonell was caught, and sentenced to be hanged under the laws of Alphonso X of Castile. Grief-stricken, his parents went to examine his body on the gallows, only to hear his voice saying that St Domingo had kept him alive. His parents then rushed to the magistrate’s house where the magistrate was eating his dinner. The magistrate declared ‘Your son is no more alive than this chicken and this rooster on my plate!’ Whereupon the rooster and the chicken jumped from the plate and crowed. The boy is pardoned on the spot and retrieved unharmed.

We don’t know if the magistrate then convicted the barmaid for perverting the course of justice…

I suspect, like many miracles and legends, this one holds a moral lesson about not rushing to judgement. And definitely not to jump to conclusions, and to check facts before sharing or cancelling people on social media. Remember, the chook might not be what you think it is!

In philosophy, this would be the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. In English this roughly translates as ‘something happened, therefore this other thing caused it.’ The cup was found in his possession, therefore he stole it. Purely circumstantial. And wrong, resulting in a miscarriage of justice.

Several locations have versions of the story in several other locations. The salvation is either attributed to Santo Domingo, St James, or the Virgin Mary (perhaps a group effort?). Barcelos in Portugal claims an almost identical legend. And the English Christmas carol ‘King Herod and the Cock’ recounts yet another somewhat similar story:

There was a star in David’s land,

In David’s land appeared;

And in King Herod’s chamber

So bright it did shine there.

The Wise Men they soon spied it,

And told the King a-nigh

That a Princely Babe was born that night,

No King shall e’er destroy.

If this be the truth, King Herod said,

That thou hast told to me,

The roasted cock that lies in the dish

Shall crow full senses three.

O the cock soon thrusted and feathered well,

By the work of God’s own hand,

And he did crow full senses three

In the dish where he did stand.

In commemoration of this miracle, the priests keep a chicken and a rooster in the cathedral all year round. They claim that the chickens are descendants of the same chickens as in the miracle. The priests swap them around every month, supported by the Confraternity of Santo Domingo, with the help of donations. A friend of ours, the author Tara Marlow, found the ‘spare’ chickens. They were in a coop behind the cathedral when she was on pilgrimage to Santiago.

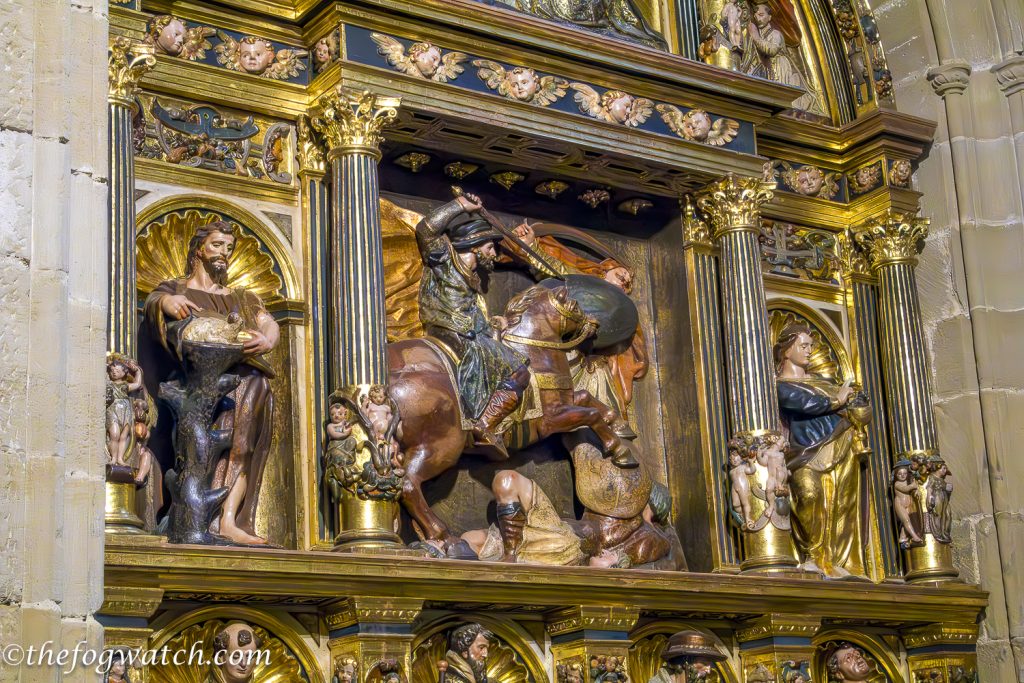

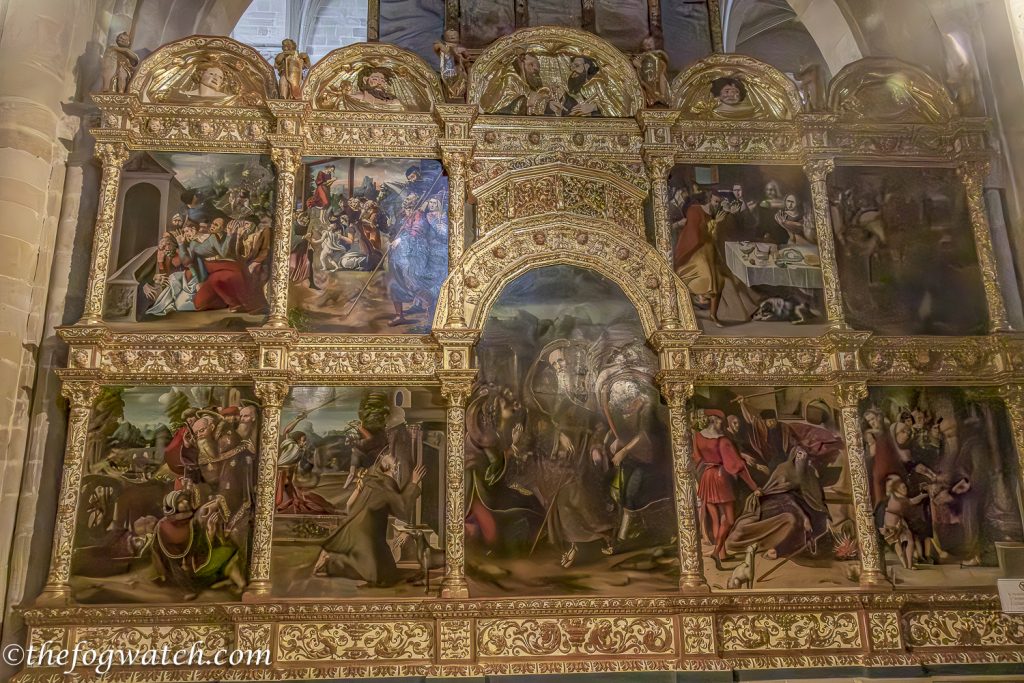

The church also has sculptural representation of St James/Santiago as ‘Matamoros’ or Moor-slayer, and as a pilgrim.

While the story of the chicken is an important aspect, as discussed in my previous blog post, there is more to this cathedral.

One aspect is there, largely unnoticed, right next to the chicken coop. Hanging on the wall, are several sets of chains and iron shackles — a somewhat gruesome reminder of the brutality of the Church in earlier centuries. These chains were used on criminals, who walked the Camino as part or all of their sentence. And having completed their sentence, they gave the shackles to the church in thanks for the completion of their penance, and their release back into the community.

There are two aspects to this. First, is that penance is about forgiveness, which could be also viewed as the other side of control. This raises the awkward question that asks: can we only act morally if we assume some kind of universal surveillance by an all-seeing God, against the risk of an intangible but truly terrible punishment after death? This is control through the double jeopardy of guilt and forgiveness. This casts the responsibility to determine what is moral in the hands of an intangible (absent, therefore unquestionable) Other who not only determines what is good and right, but also holds the power to dispense or withhold mercy. As a self-confessed agnostic, I might have a problem with that somewhat Orwellian framework.

Surely, as a species, we simply have a basic responsibility to treat each other with respect, kindness, and compassion. Because what makes us stronger as a community is when we collaborate and work together to look after each other — and the world in which we live. Indeed, in light of climate change and novel diseases, like Covid-19, our species’ survival ultimately rests on our capacity to do just that. To treat others as we would want to be treated. This is what the German philosopher Immanuel Kant referred to as the Categorical Imperative.

The other lies in the belief that self-mortification somehow brings the believer closer to God, however you conceptualise Him or Her. These days the church views the trials we face in life as sufficient penance to achieve that end. Pope Francis insists that “each believer discerns his or her own path, that they have a resonsibility to bring out the very best of themselves.” Another way to express this is that everyone walks their own Camino. And this applies equally to the Camino de Santiago as well as to the Camino of life.

There has been a lot of discussion about what constitutes a ‘true’ pilgrim, with exhortations to walk as Medieval pilgrims did, carrying their belongings. Should this include walking in shackles? or self-flagellation? I’ve seen discussions on various forums on this topic, usually starting with someone being judgemental of others.

While such judgement may make the judger feel better about their own ability to carry their pack, belittling others’ efforts does not enhance the community, and can even destroy the experience of those less physically able. So which behaviour is more pilgrim-like in the end? Only we can walk our Camino. The only ‘rule’— if you wish to receive the compostela — is to walk the last 100 kilometres. That’s it. You can have a robot dog carry your pack if you want. Or send it forward by Xacotrans or Correos, or carry it if you wish and are able. Judge not lest you be judged!

The Camino is open to all. And narrow interpretations of a ‘true’ pilgrim only serve to place unreasonable burdens on those who already carry burdens of age, infirmity, or social inequality. To those who would seek to judge the worth of others’ pilgrimage, I say: ‘Real’ or ‘true’ pilgrims don’t judge others, but rather demonstrate by their actions their willingness to reach out and comfort others.

I recalled that the Cathedral also has alabaster effigies of two early bishops of Santo Domingo by the sculptor Gullén de Hollanda, beautifully carved and highly expressive, dressed in the clothes of the time, the armour reflects the geopolitical uncertainty of the time.

The wooden carvings in the choir are amazing! — each choir stall is unique and expressive. The choir, begun in 1521 by Andres de Nájera, features saints depicted with their attributes. Grotesques are carved into the arms of each seat. The overall effect is extraordinary.

The Reliquaries are both gruesome and extraordinary with various saints’ body parts carefully preserved in effigy form. Relics were an important part of medieval pilgrimage as a potent reminder of sacrifices made for religious freedom. They were also important revenue raisers for the medieval church. The relics were viewed as having supernatural powers to heal or bring luck. So they would attract pilgrims in their own right. And of course, visitors brought more revenue to the church. The church usually keeps the relics covered, only to reveal them on the saints’s days or throughout Holy Years. Since 2022 was a Holy Year they were on display for us.

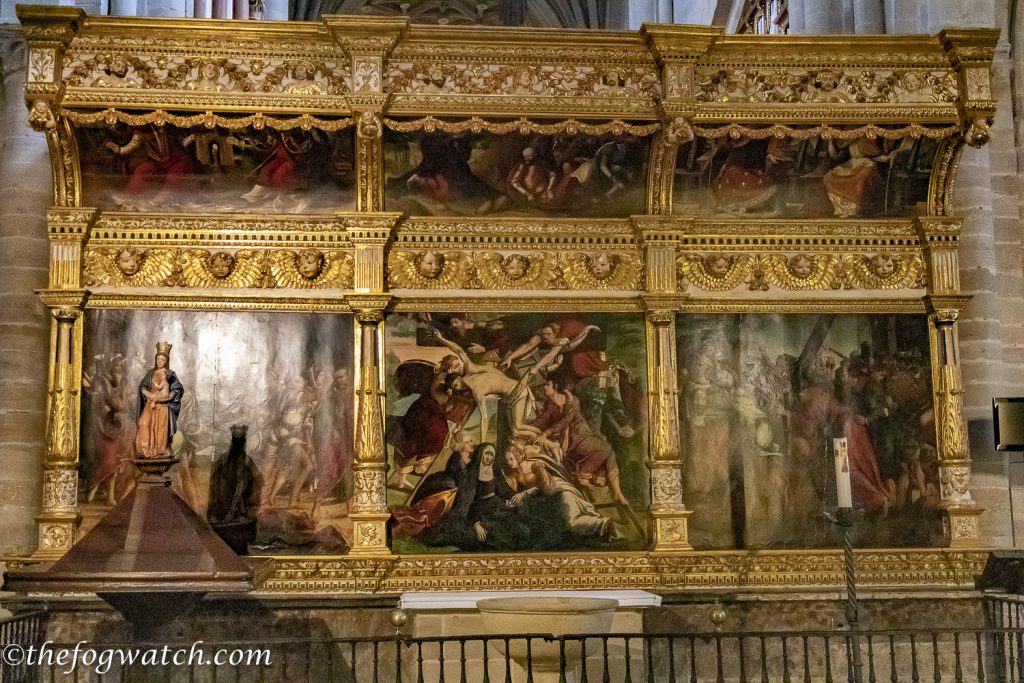

Behind the altar the retable is a series of powerful Renaissance paintings, rather than the usual gilded carvings. The expressiveness is in many ways more powerful than huge panels of micron-thick gold leaf.

The only other detail, perhaps best overlooked, is one of the ugliest crucifixes I have seen. I think a modern Spanish artist carved it in a ‘naive’ style. The church hierarchy installed it near the back of the cathedral. I felt it looked out of place, and I suspect that the church hierarchy felt the same way.

We paid our respects to the chickens, and to Santo Domingo in his cathedral. Then we headed back to our accommodation. Oh yes, did I mention the Parador? It has continuously served pilgrims for over 900 years, making it one of the oldest hotels in Europe. Our room overlooked the square and was probably the second most comfortable stay on our Camino. Our room also has an ensuite bathroom. The antique furniture added atmosphere, including a writing desk and a flat-screen TV. We barely heard the thunderstorm that raged for much of the night.

In walking from Nájera to Santo Domingo de la Calzada, we learned how having a goal in life can be truly life-affirming even when all seems lost. And through the legend of the roasted rooster we learn not to be so quick to judge someone. And of course, we are grateful that we have the resources to come on pilgrimage and experience life in a thousand years of footsteps, patterning my mind and body into new forms of health and calm.