On several visits to Europe from Australia, I passed through Frankfurt as many thousands do each day in transit to other places, perhaps stopping for a day or two. But this time was different. We had come to Europe amongst other reasons, to walk the Camino de Santiago — a medieval pilgrimage route through Spain. With a few days left at the end of our trip, we decided to make a different sort of pilgrimage — to the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz just a short suburban train ride from the centre of Frankfurt.

Here was the birthplace of moveable metal type printing in Europe. Now, that might seem a bit… well… specific. After all, didn’t he simply invent the printing press? Well, no, to put it bluntly, and the museum tells a fascinating story that includes the many innovations leading up to the appearance of the press in Europe. But the story does include pilgrims, a dodgy deal, at least three religions, Ghenghis Khan, an invasion and some pretty canny monks and officials. This story has the makings of a good Dan Brown thriller from beginning to end.

The China Connection

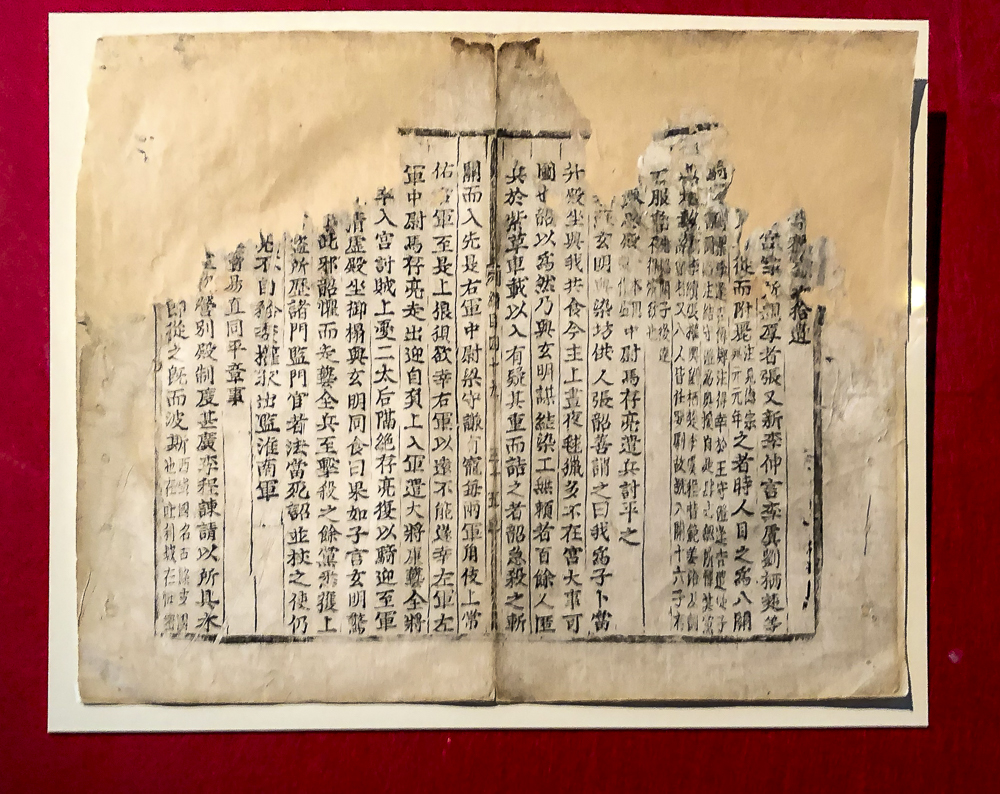

It began, of course with China back in the early 9th Century AD and perhaps a bit earlier. With over 2000 characters, it was just as easy to chisel entire pages (backwards) to produce printable book pages. Paper had been in use for almost a thousand years before this. The industrial production of paper began around 100AD resulting in an efficient and organised government. Indeed, such was the availability of inexpensive paper, that by the 6th century it was being used as toilet paper. As an aside, we know this because a Chinese official called Yan Zhitui, wrote in 589AD advising against using paper containing writings of Confucious for ‘toilet purposes’.

So the Chinese had block printing and were using presses to mass-produce books. But wood-cut blocks were prone to wear, and uneven absorption of the ink. So around 1040 an official called Bi Sheng developed a ceramic moveable type system. Contrary to popular belief, the ceramic type proved strong and resilient, even when dropped onto hard floors. And it lasted much longer than wooden typefaces, able to produce thousands of reprints without visible wear.

Enter the Koreans

Buddhism had spread through China and around 971 Chinese printers produced a massive Buddhist text called the Tripitaka using no less than 130,000 woodblocks (one for each page). A century later a copy was brought as a diplomatic gift to the Korean rulers known as the Goryeo (from which Korea got its name). And along with the Tripitaka came the knowledge of block printing.

Fast forward to 1232, when the successor to Ghenghis Khan — Ogedai Khan — invaded Korea. Soon, he reached the capital, where the invaders burned the copy of the Tripitaka. Not wanting to lose their Buddhist cultural heritage, the Goryeo rulers ordered a new copy to be made. The task was charged to a Government official called Choe Yun-ui. Despite the conservatism of the cultural elite, Choe quickly realised that making copies with wood-blocks would be an impossibly large task. So he drew on and innovated around earlier Chinese attempts with moveable type, and combined those ideas with the techniques of casting bronze coins and medallions.

A key technology

The result was an efficient method of producing large quantities of moveable metal type. By around 1400 King Sejong ordered a simplified alphabet to be devised, based on sounds and mouth-shapes. This reduced the character set to 25 and greatly advanced the ease with which the Korean language could be taught — and printed. And so the story could have ended there with Korea blazing a cultural and literacy trail across the world. But there was a problem.

The conservative cultural elites were a bit like Thomas Watson, President of IBM in 1947 who said that the global market for computers was probably 5 machines. They just could not envisage a role for mass literacy. This was coupled with the fact that Korea was again under invasion so they couldn’t just set up hundreds of print shops.

But remember those pesky Mongols? They thrived on innovation, technology and speed to maintain their empire. By now, the more stately Kublai Khan had taken power, residing in Beijing. His brother ran the Persian end of the Mongol business. At this Western end were the Uighurs – an educated Turkic people who traded along the Silk Road. And knowledge travelled with the traders. So where does Johannes Gutenberg fit into all this?

Back to Gutenberg

I mentioned pilgrims earlier on. In Aachen in Germany, the cathedral held four great religious relics collected by Charlemagne. These were later donated to the cathedral in 1220. The relics were said to include: the swaddling clothes and loincloth of Jesus, the dress of Mary and the decapitation cloth of John the Baptist, which have been shown to the congregation and to pilgrims participating in the Aachen pilgrimage every seven years since bubonic plague struck in 1349. So many pilgrims would crowd the cathedral, that locals would produce and sell concave mirrors said to catch the ‘powers’ of the relics, even if the pilgrims couldn’t actually reach them. Johannes Gutenberg had a plan. He would come up with a secret method of mass-producing these mirrors and undercut the Guilds thereby making a pile of cash for another invention he was working on.

To raise capital, he borrowed a sizeable sum of money from two partners, in order to fund the set-up and production costs of the pilgrim mirrors. He had no sooner spent the money on plant and machinery when disaster struck. Actually, it was the bubonic plague that came to Aachen and the pilgrimage was cancelled. He was barely able to raise enough money to pay back the investors. But he was not defeated. And, like many a bankrupt entrepreneur before him, he came back with another hair-brained scheme.

The Press comes to Europe

Who knows if a pilgrim or trader had brought the idea of a metal moveable type process for printing from the Silk Road. Or perhaps it was just a case of parallel invention we may never know. But by 1439, Gutenberg unveiled his printing press along with a handy method for rapidly casting type using punches and a matrix into which the casting metal could be poured again and again, with each piece identical in shape and height and interchangeable with each other. And the idea fell on fertile ground, slowly at first, then exploding across Europe.

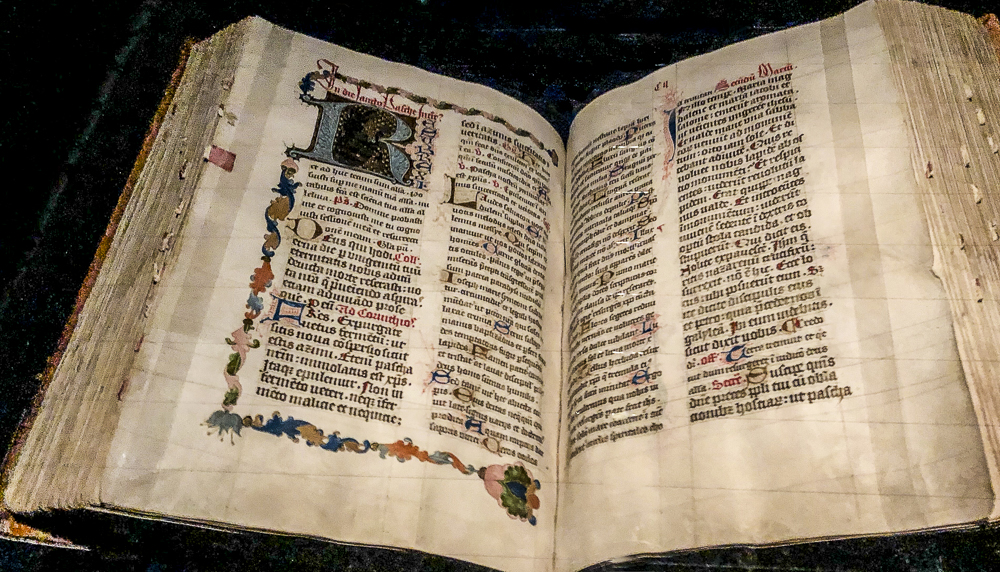

The idea was almost too slow… as. Gutenberg managed to produce some handbooks and hymnals and then the pièce de résistance, the Gutenberg 42-line Bible. It was a triumph, but slow to sell. It takes a while to create a new market. And for printing, it took the widespread spread of literacy to become truly profitable. And once again, creditors swooped and took possession of the presses, workshop and remaining bibles when Gutenberg couldn’t raise enough cash. They went on to make fortunes from the press, leaving Gutenberg struggling financially. Ultimately he was knighted and given a pension, but he was a broken man.

Outcomes

Yet his innovation arguably resulted in the standardisation of spelling, the rise of European literacy, and provided the means of mass communication that enabled the spread the of the word of Martin Luther leading to the Christian Reformation. And this is barely scratching the surface of an amazing museum in Frankfurt, housed in a gorgeous historic building just across the square from the Cathedral — Church and State separated by a common space for the people and united by a common interest in mass communication.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

At a glance:

Address:

Gutenberg-MuseumLiebfrauenplatz 555116 Mainz, Germany

Opening hours: Mon closed; Tue – Sat 9 a.m. – 5 p.m; Sun 11 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Admissions:

Adults: €5.00 Concessions: €3.00

0 to 7 years: free admission

8 to 18 years: €2.00

Hi Jerry, I had not had updates to Fogwatch for some months so am checking in again, hoping for more interesting items from you.

Hi Maureen – My apologies, yes I have been neglecting the blog a little and will be posting more soon 🙂

That is good to hear, Jerry, … apologies are never needed. Enjoy the day.

I have not been to Frankfurt but your post makes me want to go to this museum. Thank you very much

Thanks Mona – I loved the museum — well worth a visit! And I would love to revisit it when we are permitted to travel again

A very fascinating story, from beginning to end, of the Printing Press. It’s strange how we can take things for granted but never look for origins. Thank you for posting this one.

Thank you Maureen — It’s always interesting to look behind some of the things we take for granted today 🙂