I shivered in the winter chill, as the sheep grazed unconcerned in the paddock next to the giant metal dish. Magpies warbled in the distance and I wondered what it must have been like for the technicians worried, as heavy wind gusts tugged at the dish, yet knowing they were in the one place properly ready to receive the grainy TV pictures and hear those words: “That’s one small step for man… “. Fifty years ago, human beings first walked on the Moon. I felt fortunate that being in Canberra, Australia, I had the opportunity to visit several sites of significance to the Apollo space program and other space missions by taking a day tour organised by the Australian National University. Australia played a vital role in the Apollo missions as one of three locations spaced roughly 120 degrees apart on the Earth enabling continuous communication around the clock. I’ll get to that in a moment.

We met our hosts (and the bus) at the National Museum of Australia, before setting off for Mount Stromlo observatory on the Western edge of Canberra city. The observatory was set up as a Commonwealth observatory way back in 1927, though it was used as an observatory since 1911 with the arrival of the wonderful 9-inch Oddie telescope (unfortunately destroyed in the 2003 Canberra Bushfire).

Mt Stromlo became an important solar observatory, and today it is part of the Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the Australian National University. It also houses a satellite testing facility, including a large vacuum chamber and an anechoic chamber. The first is used to test components for their ability to operate safely in the vacuum of space, and the second assesses the satellite’s vulnerability to various forms of electromagnetic radiation and interference. We don’t normally get to see this facility, but it was opened up as part of the tour. The Apollo components would have undergone similar testing before being allowed to be sent into space.

Then on to the Canberra Deep Space Communications Complex (CDSCC) at Tidbinbilla – a joint facility between NASA, CSIRO, and JPL. We were shown around by Glen Nagle, the Outreach and Public Relations Manager at the CDSCC at Tidbinbilla.

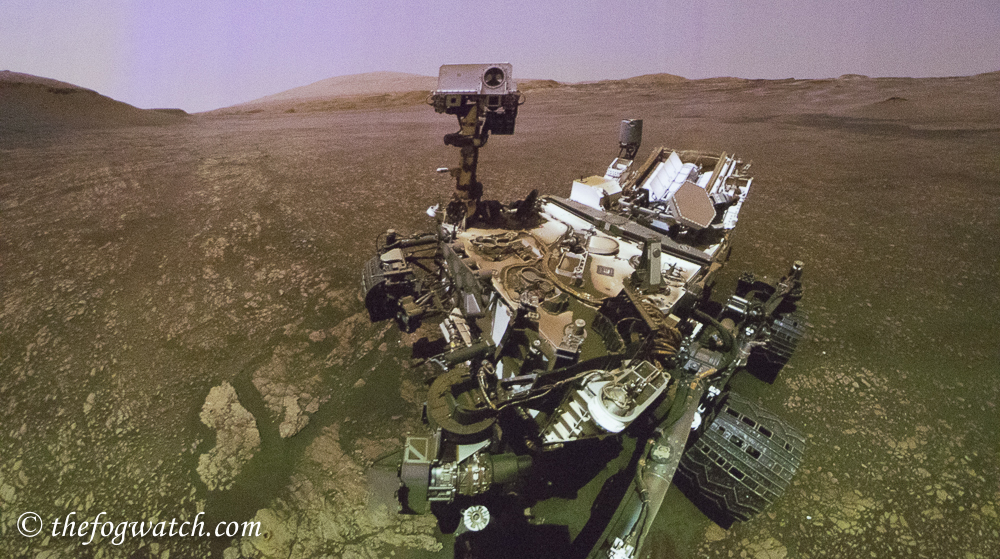

Along with similar facilities in Pasadena (USA) and Madrid in Spain, they form the Deep Space Network. We had the opportunity to see images fresh from the Mars Curiosity rover – it was intriguing to find that the Martian sky is red during the Martian day, but blue at sunset – the reverse of our sky on Earth. The large 70 -metre dish (43) is still able to receive signals from the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, the two furthest artificial objects sent into space. Eventually, they will be so far away that their signal will be lost in the background noise of the universe. You can see what is being tracked in real-time by each of the dishes on the network (Canberra, Madrid and Pasadena) here.

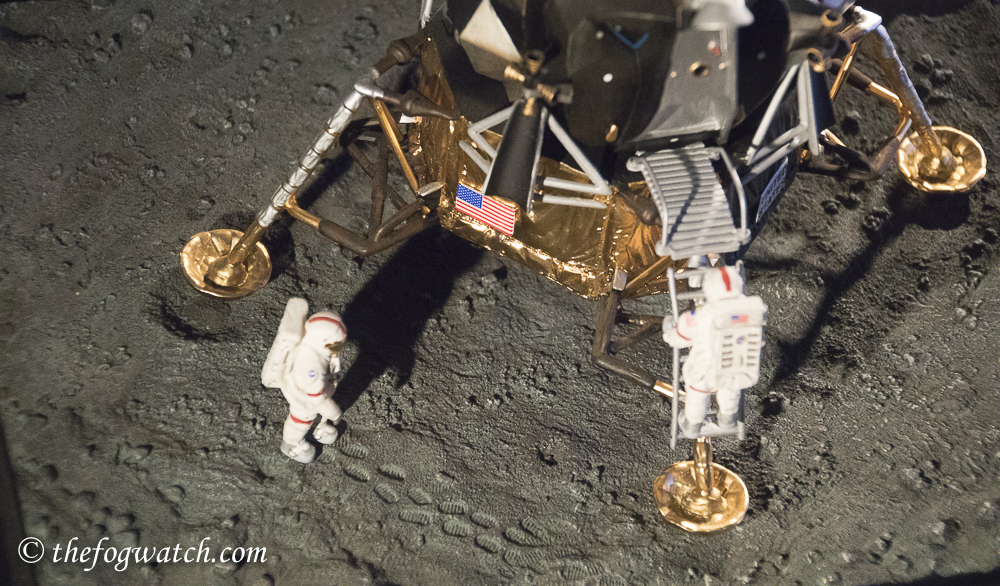

CDSCC also houses the largest piece of Moon rock on display in the southern hemisphere – a piece of rough basalt brought back by Apollo-11. It is quite rough to the touch – some years ago it was possible to touch the rock, though today it is locked away behind security glass.

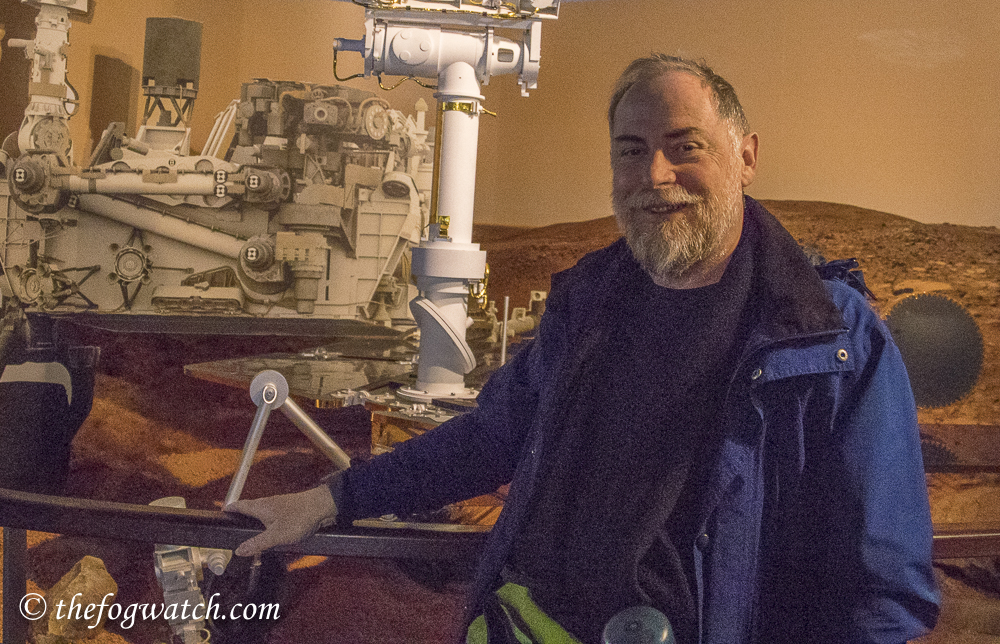

Of course, I had to get a selfie in front of the full-scale model of the Mars rover Curiosity

Back to Apollo-11 – the first TV signals beamed around the world of Neil Armstrong’s descent down the ladder of the lunar landing vehicle, and the famous words: “That’s one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind” were picked up by this dish (below) at Honeysuckle Creek just south of Canberra (not Parkes as the movie The Dish would have you believe). Because the astronauts decided to step out early, Honeysuckle Creek with its higher altitude and clearer horizon, was best placed to pick up the first signal. Interestingly, the Goldstone station in the US also received the signal, but due to a switching error, their image was upside down. Parkes did receive and distribute the TV signals from the moon, once the moon was sufficiently above the horizon a few minutes after Honeysuckle Creek, and with its larger dish, received better images that were then beamed around the world. The clarity and strength of the Australian signal meant that that was the one to be broadcast around the world (no pressure…). The movie was accurate in that high winds made life difficult both for Honeysuckle Creek and for Parkes. In both cases, the dish acted as a huge sail and they were not designed for the wind gusts they experienced. But with so much at stake, they persevered and the dishes survived – and they got the pictures!

Not much remains at the now decommissioned site, other than the foundations for the office buildings and the footings for the dish. And of course the sounds of cockatoos and magpies.

But the dish survives and was relocated to Tidbinbilla where it could be better maintained and cared for. Glen Nagle told us that when Apollo 17 astronaut Eugene Cernan visited a few years ago, he saw the Honeysuckle dish and said that not much Apollo infrastructure survives – “don’t let anyone get rid of this one”. And yes it will be preserved to commemorate the Apollo missions that it supported.

A sculpture commemorates the Apollo 11 landing and Australia’s role in it by displaying the words “One small step – One giant leap”

Finally, we visited Geosciences Australia where they have a piece of moonrock you can touch – so yes, you can touch the moon! This piece was brought back by Apollo 17 – it is smooth to the touch. The rock was collected from the Taurus-Littrow valley on the moon and is comprised of a titanium-rich basalt. It must have cooled quickly as the crystal structure is very small and closed, unlike other moon rocks that have a more open structure. The so-called seas (Mare) on the moon appear smooth, but they are the result of rock being liquified from enormous impacts and then setting smooth like giant lakes of molten rock. So, far from the ‘Sea of Tranquility’ (Mare Tranquillitatis), the Apollo 11 landing site was actually formed from extreme violence.

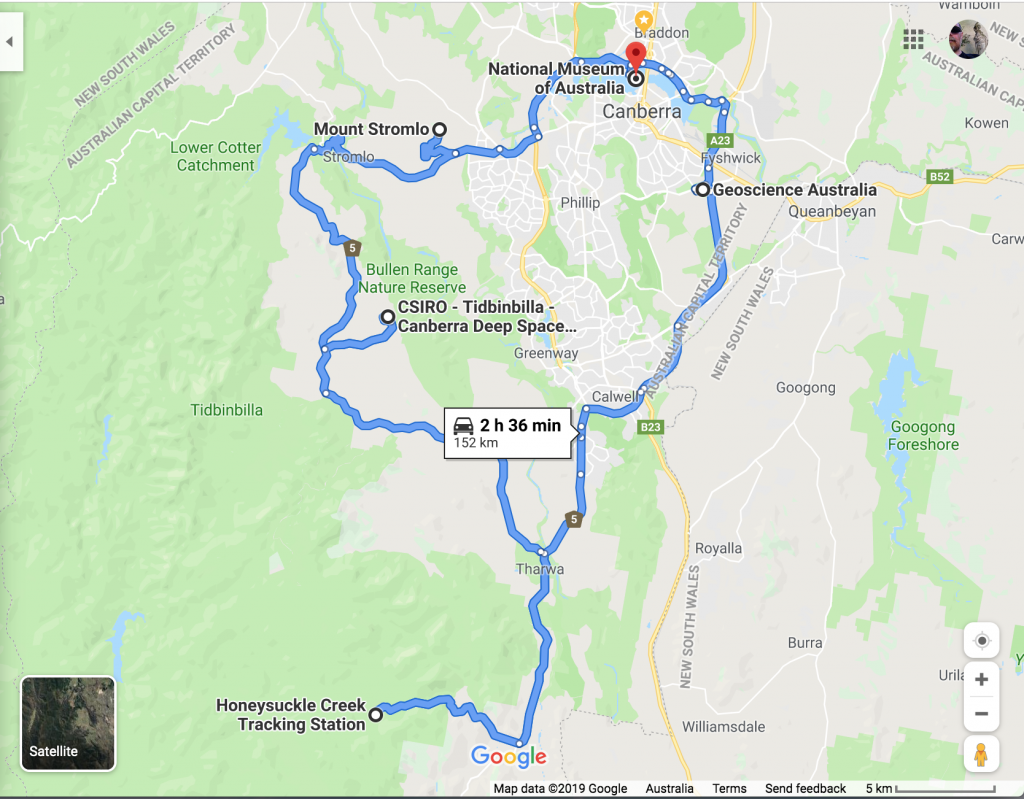

To follow in our footsteps, here is a handy Google map of the main locations in this post:

There are a number of events around the world commemorating Apollo 11 – it’s well worth checking out what is on in your local area. You would be surprised at how your backyard may be linked to global events like this. Leave a comment below on places you have been that are linked with the various space programs.

Thanks, Jerry, I knew Australia was involved but did not remember to what extent. As it happened, on that memorable day, I was at summer camp where we all sat around a campfire and stared at the moon – so very low tech and something I’ve never forgotten. Exciting times.

Nice coverage Jerry. Makes one a bit nostalgic for dear old Canberra.

Thanks Tim – yep it’s not a bad spot 🙂

this is wonderful, like the NASA radio site! you might want to explore vlf radio someday – it’s not difficult and the results, cosmic/atmospheric, are amazing

Best, thank you, Alan

Thanks, Alan – There are many hidden gems if we go looking for them. As for the radio, I have sometimes thought about VLF radio, but I have way too many other interests on teh go at the moment.