Burgos Rest Day — Meet the relatives

Today is about beginnings.

The day dawned. Which is fortunate, because if it hadn’t it would have ruined our whole day. And it was a rest day, so we had stepped out of Camino slow-time and into the fast pace of modern Burgos. It’s time to visit the Museo de la Evolución Humana (MEH) but it is far from a ‘meh’ kind of place.

Meeting the Relatives

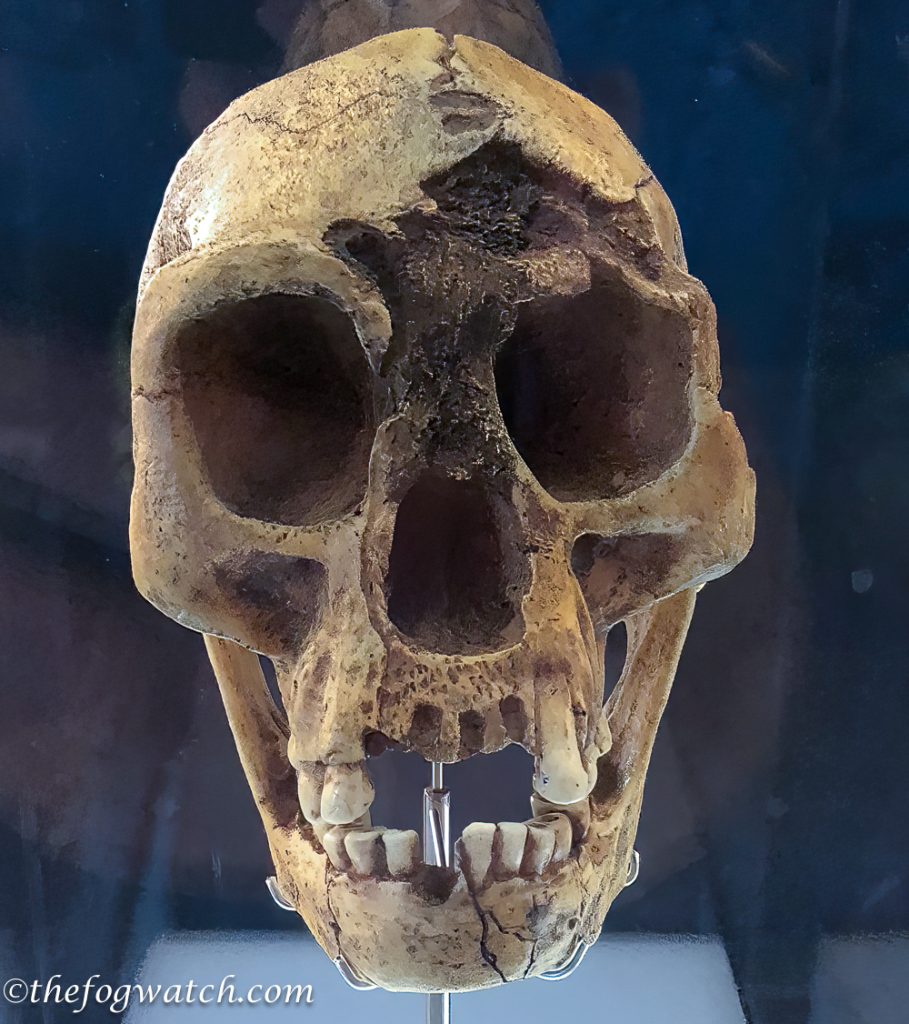

I stood transfixed at the skull of the person standing before me, and wondered at the 800,000 years that connected and separated us in that place and on that path. The skull of Homo Antecessor was found at Atapuerca, just 20kms away, along with other hominids, like this one below, of Heidelbergensis. And now, somewhat improbably, I found myself at the Burgos Museum of Human Evolution.

“Do you know why you are here?” it asked

“This could take some time” I responded, then looked around the darkened room, hoping no-one overheard.

Spain is full of intersections and coincidences that seem like the sort of Fate that I tried not to believe in. Yet here I am. Nearly halfway across the country, talking to the skull of a corpse in a museum. But then, Spain is like that. Enriched with magical realism, like a Marquez novel or perhaps Cervantes. On the Camino, sometimes our internal voice becomes externalised, so that we can better know ourselves in the Socratic sense. That’s my excuse anyhow.

“It’s about time!” said an actual voice in the darkness.

“I think you’re right,” I said to my wife. We had walked more than 300kms together, and it was time for lunch. You could smell the rain coming, and it hit us, cold and wet, as we crossed the bridge and headed for the square.

“When did it start?” she asked over medieval lentil stew

“The rain?” I said absently

“No, the Camino — when did it start for you?”

I remembered the email, suddenly — an invitation to a ‘Wellness’ seminar at work. That was over eight years before our first Camino. A young work colleague and her partner had walked from Leon to Santiago de Compostella in Spain taking an ancient pilgrimage route. The photos were holiday snaps of villages untouched by modernity — with churches and ancient forests — well, more like selfies in front of these things, but their hike was at least more interesting than some of the New Agey sort of things usually presented in these seminars.

And then my mind was back in the museum, telling the story of the very beginnings of humanity. It’s about time. It’s about the human connections that we forget about in our daily lives, and the way some intangible thread connects us all way back into the deepest pre-history of our species. Deep time.

At one level, the Camino perhaps began 65 million years ago when the Iberian sub-plate, part of the African tectonic agglomeration, collided with the European plate resulting in the enormous uplift we now call the Pyrenees. And to this day the Pyrenees is getting a little taller each year as the collision hasn’t finished yet. I guess that’s why I feel more tired each time I cross the Napoleon route.

It’s also why you can sometimes find fossilised sea shells high in the Pyrenees the way I didn’t on this occasion.

Without that event, the people that came to inhabit the area would not have been separated by the Pyrenees from other Europeans, thereby developing their own culture and languages — Portuguese, Galician, Cantabrian, Catalan, Basque, and many more. In turn, these were influenced by waves of immigration and conquest — the Celts, the Romans, the Moors, and the French — each contributing to the culture that became uniquely Iberian.

And St James would not have been able to go there to preach, only to be executed on his return to Rome. And his body would not have been brought back to Spain to be interred in a Roman cemetery to be discovered after several hundred years — if you believe the legends — in time to repopulate the northern part of Spain with Christians as part of the Reconquista to drive the Moors and Berbers further south and back to North Africa. Geopolitics and Christian mythology collide here, and we as latter-day Don Quixotes tilt at the windmills of our mind on this extraordinary journey.

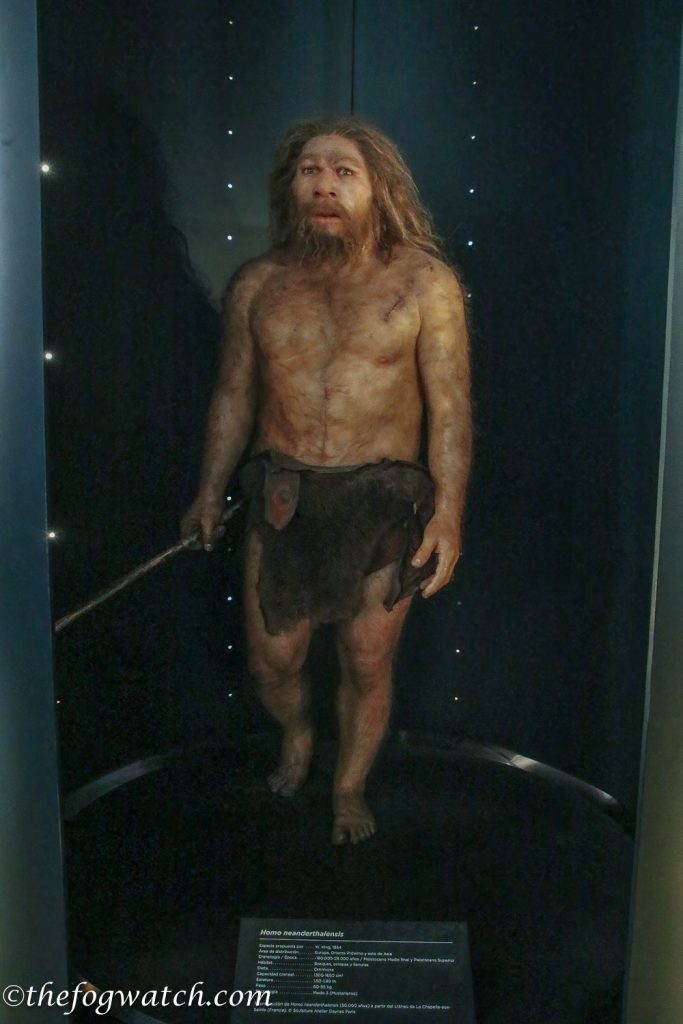

The Museum of Human Evolution houses the finds from Atapuerca, as well as excellent reconstructions of the appearance of various human species predating modern humans found in the area. Atapuerca, was not only one of the last places the Neanderthals survived — co-existing with modern humans for around 50,000 years — but also the site yielded Neanderthal predecessors, Homo Heidelbergensis and Homo Antecessor, dating back to 800,000 years ago, and other hominids as far back as 1.2 million years.

This day coincided with a celebration of heritage, so entrance to the museum was free (normally half price for pilgrims). Many artifacts were on display, as well as displays of the Atapuerca dig structure, and reproductions of cave paintings that were found at Atapuerca.

The human story is well told, both chronologically and thematically — this is a world-class museum. There were copies of bone flutes from 30,000 years ago. These suggest that music was an ancient part of life, perhaps second only to language.

Painted decorations on cave walls suggest a symbolic life and research suggests that H. Heidelbergensis and Neanderthals were both capable of speech. This is based on the skull structure and placement of the windpipe and the oesophagus — the placement meant that it was possible in both cases for individuals to choke on their food. To avoid this, they needed a well-articulated tongue and the capacity to close the windpipe to ingest food and drink — and of course to talk. The ability to do this means that you can produce a wide range of sounds with a large degree of sophistication. This points to an ability to speak.

While we know little about the Denisovans, we know a fair bit about Neanderthals, and in particular, that they were very conservative, changing little in their behaviour, and toolmaking over long periods of time. They lived in small groups and kept within a small geographic range throughout their lives. Their trading range appears to be not much more than 20 miles or so. However, the average early modern human traded and ranged over at least 120 miles. Modern humans lived in larger groups, providing greater genetic diversity, and therefore able to draw on a wider range of experience, so as the climate changed, we were better adapted to deal with the changes in food sources, disease vectors, and changing weather patterns. It is also likely that there were at times violent encounters as resources became locally scarce, but evidence for this appears to be scant.

The flint tools in the museum ranged from fairly crude and roughly shaped hand axes to finely made arrowheads and specialised scrapers, knives, and axes, the latter shaped for binding and securing with resin to a wooden handle to increase leverage.

Tool making indicates, not just technical skill, but abstract thought. In order to make a tool, you first need to conceptualise what the solution to a problem looks like, then imagine the tool to meet that need. And finally, you make the tool and work out how to use it effectively, and then through an iterative process you refine the tool so that it is best suited for the task at hand.

At some level, there is an analysis of the problem and a vision of how to augment the human body with tools in order to solve a survival problem. This can be how to kill for food or defend against predators. But also how to carry water or make fire. And these solutions then need to be communicated with others so that the tribal group or community can survive. Fire has been in controlled use for cooking, spear hardening and clay firing for tens of thousands of years. And there is evidence for fire more broadly being in controlled use for around 500,000 years — long predating modern humans.

So in language terms, Neanderthals likely used at least concrete terms to deal with physical conditions. The shape of the braincase suggests a highly developed visual cortex, the language processing in their smaller cerebellum less so, meaning it is possible that they had many terms for articulating the concrete world, but fewer metaphors that require the higher-level language processing available to modern humans. Having a socially restricted range likely also meant a much greater localisation of language terms and thus a much greater number of Neanderthal languages. This would have inhibited the capacity of different Neanderthal groups to communicate with each other, thereby restricting the flow of information, trade, and cognitive exchange.

“Of all human traits, symbolic language is the most unique to humankind. From figurative art to funery rituals, it is one of our most important cultural acquisitions. Symbolism demonstrates the complexity of the human mind and its capacity for abstraction … In addition to communicating a group’s symbolism, [works of art] constitute an experience shared by all its members. Art reflects all of our mental assets.” — Museo de la Evolución Humana

Today we augment the body, not with worked flints or animal skins, but with trekking poles and lightweight backpacks and enhance our senses with spectacles and smartphones that extend our ability to communicate with others, or pattern our brains with music, mediating our experience of the world around us. Of course, this can be at the expense of actually communicating with those present with us. The trick is to use these enhancements sparingly so that we focus more on the present, and take note of the world around us. The Camino is a space out of time, providing an opportunity to simplify and be present.

When modern humans arrived on the scene, there were several other human species. By 50,000 years ago we were down to three, and by 40,000 years just homo sapiens remained. Modern humans interbred with at least two other species, Neanderthals and Denisovans. Both species likely contributed important aspects of our immune system. They were survivors. And they were in Europe long before modern humans and had developed adaptations to endemic bacteria and viruses. Today we have 1-3% Neanderthal DNA as markers of this interbreeding. This quantity of DNA tells us that there was more than isolated interbreeding with Neanderthals.

Did we wipe out those other species? Probably not, but modern humans did have some competitive advantages. It appears that climate changes accounted for most of the depopulation events, with Neanderthals and Denisovans taking the silver and bronze prizes respectively.

We don’t know whether the Sapien/Neanderthal interbreeding was a consequence of conquest or social contact. But it is clear that Neanderthals greatly improved the sophistication of their tool-making and symbolic mark-making during their last 50,000 years, when modern humans interacted with them. In the end, the last Neanderthals died out in Northern Spain and Gibraltar.

You can take day tours from the museum to the archeological site at Atapuerca, although the tours are held only in the Spanish language.

It is extraordinary to think that this land has supported countless generations of human occupation reaching back more than a million years, surviving several cycles of ice age and thaws and very substantial climate changes. Will we be as adaptable to the more rapid climate change we ourselves are bringing about?

We had much to discuss over dinner, as we enjoyed Castillian soup. This was followed by entrecôte (boneless rib steak) on a sizzling iron platter, garnished with french fries and Castillian peppers. Just a tip here, if the choice is available, go for the €19.00 menu, rather than the €14.00 one. This was at Restaurant Don Nuño on the main square. Dessert was cheesecake — a real baked one with no gelatin in sight. This was all served with an excellent vino tinto 🙂

So to sum up the day. The finds in Burgos and the surrounding region remind us of our connection to deep time and to each other. The Camino weaves a story across Europe and across the globe, and we are walking our way into that story, becoming part of it, and it in turn becomes part of us. Sometimes we need to slow down to experience deep time by immersing ourselves in a period of slow time.

The next few days on the Meseta will give us the opportunity to experience slow time. Here, we can begin to integrate what we have learned so far as we cross this land step by step.

Although this was a rest day, the Camino has a way of bringing the mind to consider connections across space and time. It reminds us of our common humanity. There is much here to take away and for us to ponder as we embark on the storied Meseta. It is a place of slow time, of time out of time. It provides a space for us to regain our perspective on what is important in life, and to enable us to reach into our subconscious for answers to questions we had not thought to ask in the hurly-burly and headlong rush of our daily lives at home. Perhaps that’s what the Camino is about: Time.