With Sahagun in our thoughts, we woke early, refreshed and with a sense of anticipation. We were on the road by 7.00 AM and heading out of Ledigos, hoping for breakfast. The next town, Terradillos de los Templarios — Templar territory, seemed promising. The well-made track paralleled the highway, carrying the hopes of the nation. The knights of the road saluted us with air horns — a nice gesture if it didn’t startle us out of our skin every time. We waved back with a “Buen Camino!” while trying to recover the thread of the conversation now lost, and laughed.

Templarios turned out to be a small hamlet. The Albergue/bar looked to be closing up after disgorging its load of pilgrims blinking into the light of a new day. Breakfast was as elusive as shade on the Meseta at midday.

Moratinos is a place with a name suggesting that here were Moorish settlers, Moriscos. These were Moslems who had nominally converted to Catholicism, and were subsequently displaced from Andalucia. Many settled in the flat lands of Castilla to become farmers and builders— hence contributing to the Mudejar-style of building seen in some churches in the area.

The bar provided a hearty breakfast of bacon and eggs on toast, with coffee and orange juice. Thus sated, I let my eyes wander across the road with me following close behind, as a large hill rose up riddled with Hobbit-house-like bodegas or wine cellars. Each is owned by a particular family and they have been passed down through the generations for upwards of 500 years. Each family produces enough for their own consumption, and ownership is held by strict tradition. Some suggest they go back to the Roman occupation nearly 2000 years ago. Most are now deserted, with families having died out or moved on, but two or three are still in regular use today. So no Hobbits here, but a fascinating trace of history etched into the landscape.

And there was a chair. Like something out of a magic realist novel, a lone chair stood sun-bleached at the top of the hill, staring into an unseen distance of a thousand years. It was tempting to read an unwarranted significance into this presence, shaped around the human form — a trace of a person who isn’t there. But sometimes a chair is just a chair. The Camino is like that sometimes.

Approaching San Nicolas del Real Camino (St Nicholas of the Royal Road) I looked for a sign and decided the Camino had provided when I looked up from our conversation with an Austrian couple, to read: “I know that I know nothing, but the 2nd bar is cool — Socrates”. I figured Socrates knew a thing or two… about bars. And he wasn’t wrong. The second bar served excellent cakes and some of the best orange juice we’ve had so far. We drank tea like parched desert soil in the rain — but it tasted much better.

We saw a couple of ancient Camino markers — they were here long before the Camino’s recent revival.

The track continued to run alongside the freeway until it didn’t. Entering Palencia, we turned at the marker, by a grove of trees, and crossed a small medieval bridge built over a Roman foundation. Before us stood the Ermita de la Vergen del Puente — the Virgin of the Bridge. It is a small Romanesque chapel. In medieval times, it was the site of an Augustinian-run pilgrim hospice and a pilgrim burial ground.

And then we saw the sentinels marking the traditional halfway point between Roncesvailles and Santiago de Compostela. On one side stands Leónese king Alphonse VI “The Brave”. And on the other, Bernardo de Sedirac, Abbot of Sahagun and a member of the Cluny Order. Already I was picturing a scene in The Neverending Story and mentally hearing Engywook say: “The Sphinxes’ eyes stay closed, until someone who does not feel his own worth tries to pass by” [otherwise laser beams will come from their eyes…] But back to reality, we revelled a little while in the moment before following the path into Sahagun.

Realising that, like the Winter Solstice, we had indeed crossed a threshold. There is now less distance to our destination than from our departure point. From here on, the space behind us is greater than the space in front of us. With this turning point, what have we learned? It is like that moment when you realise that you have lived more years than you probably have left. Similarly, we could reflect on the nature of time. The distance we have traveled thus far is in the past, and now unchangeable. In front lies the future, which hasn’t happened yet. And here, now, is the present where we can act. And how we choose to act will shape our future in ways we cannot yet imagine.

The Stoic philosopher Seneca points out that: “two things must be cut away: fear of the future, and the memory of past sufferings. The latter no longer concerns me, and the future does not concern me yet.”

We cannot change our past any more than we can change the direction of the footprints we have made in the mud, so regret has no place other than to redirect our future footsteps. Similarly, the future has not happened yet, and may never happen in the form we worry about, so there is little point in being anxious about the future.

That said, anxiety exists in useful part to remind us to envisage possible future risks. This way, we can take pre-emptive action to avoid the future we are most anxious about. But beyond that, it serves no purpose. What truly matters is how we act in the present, as this will shape the future and take us forward from a past we cannot change, to a future in which we can strive to be our better self. The decision on how to act is always now. There is no non-decision, as that is merely a decision for the status quo.

Despite the appearance of isolation, Sahagun has been a significant town since Roman times. But first, let’s find a café con leche and our accommodation, off on a side street. The place is called Hostal de los Balcones — and yes, it had a balcony. It is not well marked at ground level, so we went to find a local. We were eventually steered in the right direction by a guy in a bar. He asked where we were from, and I said Australia, and he immediately made the sign of the cross — either acknowledging our pilgrimage or warding off Covid. I’m not sure which. But most locals do seem glad to see the return of pilgrims to the Camino.

Sahagun is a sizeable town, once rivalling Burgos or León in both size and importance. It is still a regional hub with a pictureque reailway station and all services. And of course, you can get a halfway certificate here at the tourism office located inside the municipal albergue.

In 2022 — just after the pandemic — Sahagun felt more like it’s surviving rather than thriving. People looked worn and stressed. Bars were understaffed, often reduced to family members only. The pandemic his Spain hard.

Gertrude Bone, who traveled with her husband through Spain just before the Spanish Civil War remarked of Sahagun:

“It is an unfastidious place, the plaza, with its excellent Spanish habit of raising the first floor upon a colonnade and thus giving shelter from sun and rain to those whose business is with the market or shop below. The constant passage of saddle beasts, of riders and flocks, gives to the streets the appearance of country roads which have somehow become entangled in a town. Old women sit in charge of pimientos and melons, Fresh fish comes by the train.”

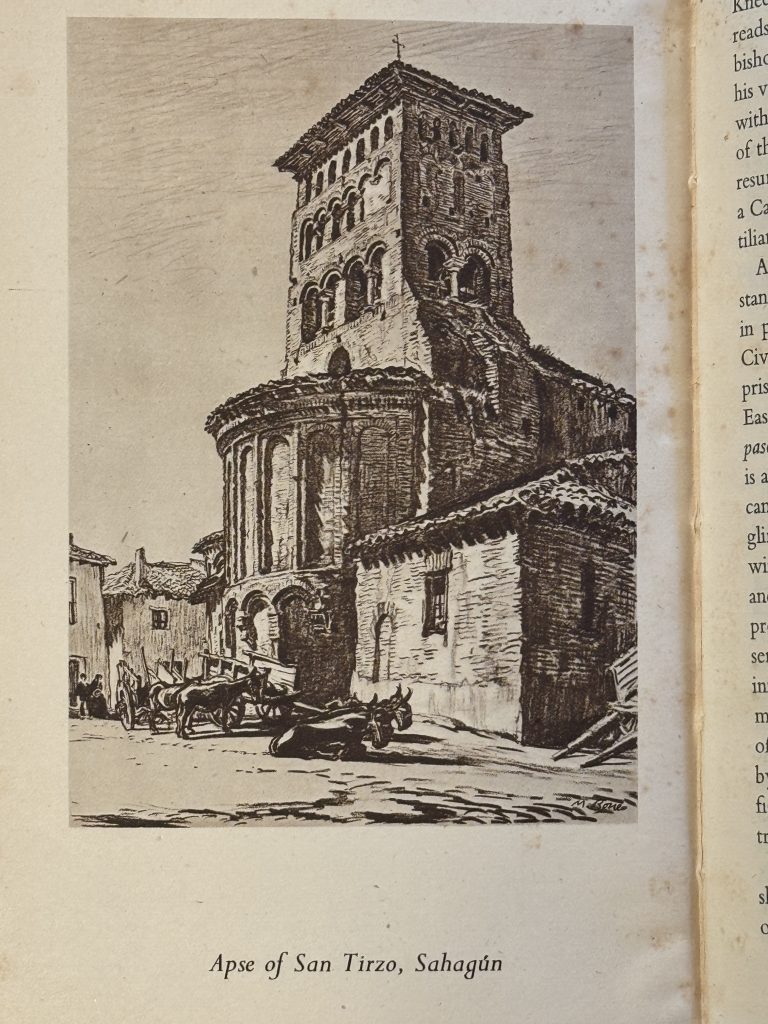

Her husband, Muirhead Bone was a much-respected Scottish War artist, and he provided some illustrations for her book. This is how the church appeared in the early 1930s compared with today:

Little has changed, other than the means of transport…

The town has had many fluctuating fortunes through the ages. The Italian pilgrim Domenico Lafffi, when he passed through in 1670 noted:

“At Sahagun, the walls were covered with so many locusts that it made a pitiful sight. When we entered the town, we found women sweeping them away and killing them with wooden bats.”

The C12th Codex Calixtinus found the town in more prosperous times:

“Then, there is Sahagun, abundant in all kinds of goods, where the meadow lies where they say that the shiny spears of the victorious champions of the glory of our Lord were driven and then flourished, is located” [referring to a miracle in which the Christians after battle drove their spears into the ground and they sprouted into a fertile crop].

Of Castile in general, the Codex Calixtinus notes:

“This land is full of treasures; it abounds in gold and silver, cloths and the strongest horses, and it is fertile in bread, wine, meat, fish, milk, and honey. Nevertheless, it lacks trees.” It also lists the river Cea as being good to drink from.

But let’s notice one thing here from the Codex Calixtinus. It’s a small but important detail. The codex speaks of this area “abounding in gold and silver”. This is three hundred years before the Western discovery and Spanish subjugation of Central America. So, when you look in the cathedrals at the sumptuous micron-thick layers of gold over the altar retables, it’s worth considering that not all of the gold came from Spanish cruel plunder from the Americas, but much of it probably came from Spain itself. Indeed, this is one reason why the Romans conquered their way across Spain a thousand years before the Christians established the Camino.

So Gallician gold is a major reason we have a long straight road across the Meseta today. On this depended the stability of a fractious nascent post-Republic Rome, and the emergent leader, Octavian, known as Caesar Augustus. He was Julius Caesar’s great-nephew and adopted heir. And following Julius Caesar’s assassination, he fought his way to power against Brutus, Cassius, and Mark Antony, as the line of succession was not clear. After brutally putting down these contenders, Octavian had himself declared Augustus, or Revered One. No longer first among equals, but from now on, emperor.

It was a quick propaganda makeover. But it worked, and he set about reforming the Government, the Army, the architectural shape of Rome, and even Rome’s cultural identity. But wars and reforms were expensive. And despite leading the way to the Pax Romana, his advisers had to tell him that … er… Rome was now bankrupt. With few funds to pay the mostly mercenary Army, the glint at the end of the aqueduct was Gallician gold.

Augustus, as Octavian was now known, led his army into the Second Cantabrian wars and conquered his way across Spain. Towns like Astorga were named after him, and 20 km out of Ponferrada, he oversaw the construction of the largest open cut gold mine in the entire Roman empire. Of course, the Roman army also brought Christianity, and soldier-settlers who set up farms across the Meseta now that there was a good all-weather trade route for barley, wheat, olive oil, and of course, wine — oh yes, and gold.

These roads were still in regular use when the Moors used them to fight their way across the Iberian peninsula, and they were still in use when the Christian Franks set about reconquering the country. And of course the pilgrims, like ourselves still use them today, in some cases paved over, but the foundations are Roman. But more on that in another post 🙂

From Ledigos, we found breakfast with Moorish descendants and lunch at a bar recommended by a Greek philosopher, to find ourselves at a pivotal halfway point on the Camino, passing through a portal into our future.