Boadilla beckoned. We rose before dawn and took a couple of photos of the castle on the hill above us. The Codex Calixtinus mentions the town, reminding us we are on the correct path.

We packed quickly and set off out of the town towards Alto de Mostelares. We were about half a kilometre out of town when sciatic pain caused us to rethink the wisdom of walking, so we hobbled back into the town. This gave us the opportunity to visit the church, before finding the cafe we ate at last night.

The church of San Juan de los Caballeros in Castrojeriz is a C13th fortified Gothic church which seems fairly plain on the outside, but look inside. Behind the altar is a spectacular gilded and painted retable from the Flemish artist Adriaen Ysenbrant, dating from 1530.

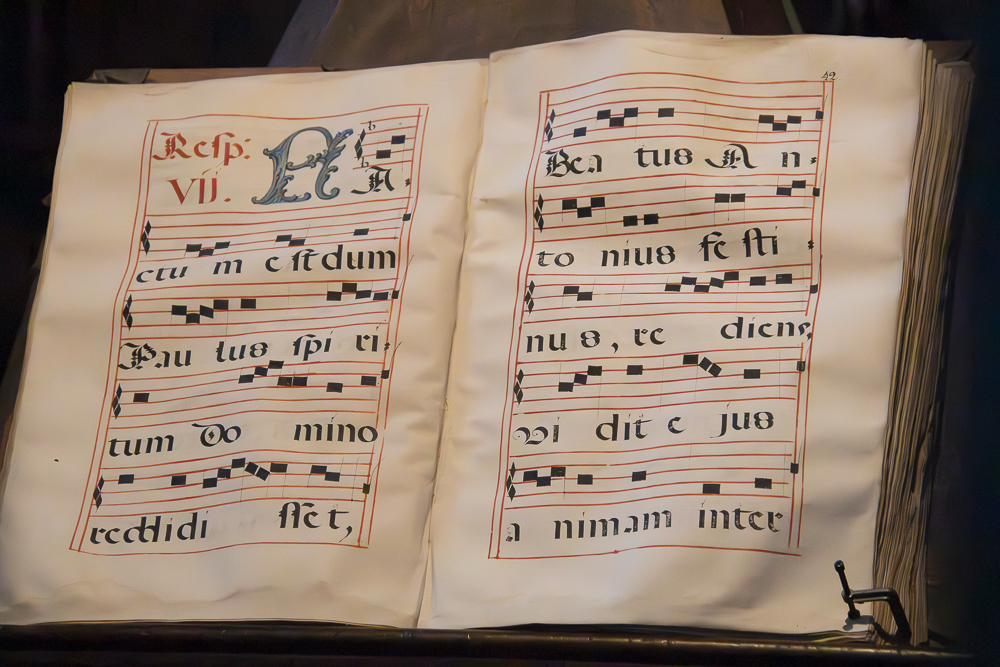

The choir contains beautifully carved stalls. In the centre, on a lectern, sits a hymn to San Anton (Saint Anthony). The massive hymnal uses a five-line staff, so this book was made after the 14th century.

Near the church stands a large Tau symbol — a symbol for San Anton.

After a cup of tea and a freshly-made tortilla de patata, we asked the server if he could call a cab for us. Another pilgrim, an Irishman, overheard and asked if he could share the cab to Boadilla, to which we readily agreed. We have walked this section before, and our priority is to put health before pride.

And so we crossed the border into Palencia.

Boadilla itself is a small village with a few houses, an albergue, and a church.

The church has a C9th baptismal font and a wonderfully decorated retable behind the altar. I lit a candle for my parents there.

We found the bar where we are staying tonight — En El Camino — a real gem. It even has a lift (elevator in American language)! And our room had a spacious ensuite. The manager was truly amazing. He speaks at least 5 languages and shared jokes with the patrons in at least three of them!

Although the Boadilla is small, the main square holds an elaborately carved column. This commemorates the granting of a charter of rights of independence from the lords of Melgar and Castrojeriz by Count Enrico IV in the C15th. The column stands where originally a Gothic gibbet stood from which to hang their own local malefactors without any noble intervention. In the C16th the authorities used the pillar to chain up offenders for public retributive justice. That would have been a rough time to be there! And that also explains why there is a smooth patch in the lower part of the column. It was worn down by the chains of the unfortunate miscreants.

We walked the extent of the village — there was no shop, just the bar/hotel. The salad for lunch was delicious, as was the excellent communal dinner.

We spoke with a Danish woman called Fria, and a Swiss woman who walked from Geneva. She will walk to Finistere and Muxia after Santiago – quite a journey!

Boadillo is mentioned in a C10th document, but may be much older and was likely part of the Roman trade route. The Codex Calixtinus says of this region:

“The land of Castile and Campos — this land is full of treasures. It abounds in gold and silver, cloth, and the strongest horses, and it is fertile in bread, wine, meat, fish, milk, and honey. Nevertheless, it lacks trees and is full of wicked, depraved men.”

I doubt the latter these days, but the food is plentiful and the agricultural lands are rich in harvest.

A massive stork’s nest sits on a stand on the church roof. It held a couple of young storks in the nest waiting to be fed by their parents.

The circular layout of the roads shows where the town’s medieval fortifications once stood. During that time, it was a major stop for pilgrims. The town once boasted a monastery and four churches.

We visited the C16th church of Santa Maria de la Asunción, which stands next to the commemorative column or gibbet in the square.

You can see dovecotes in the fields around Boadilla. These served three purposes. Firstly, the doves ate the insects that could otherwise decimate the crops; their droppings provided guano for fertiliser for the fields, and of course, the doves themselves were a source of food. The dovecotes are either circular or rectangular with niches in which the birds can nest.

On the top of one building, we saw a weather vane shaped as a blacksmith — perhaps a smithy once stood there ready to repair carts, make agricultural implements, and of course, shoe the horses. Which brings us back to the journey at hand.

What drove medieval pilgrims to walk across this wide open plain? Medieval people integrated faith and reason. Spiritual things were taken literally as something tangible. Life was to be lived in anticipation of a better life after death, and suffering was tolerated towards that better life.

I think we all need to feel part of something greater than ourselves. In walking the Camino, we are writing our story into that of the thousand years of pilgrims who have gone before us and who will walk in our footsteps in the years and centuries to come. That sense is what gave us the great cathedrals and other achievements that took decades or centuries to build. This need is the difference between shaping a stone, building a wall, or building part of a cathedral to stand long after we are gone.

We set off from a town named for its C10th castle before our bodies prevented further walking. But this gave us the opportunity to explore the church before taking a sensible rest by cabbing to Boadilla del Camino. Sometimes the Camino gives us what we need rather than what we want. Our journey today took us to a town with a remarkable, if sometimes cruel history, perhaps a lesson that it is healthier for a society to have restorative rather than retributive justice.