There was a light drizzle as I turned down a fairly nondescript Georgian side street in Bath when I noticed a plain sign outside a terrace house about halfway down. The sign read: “William Herschel Museum”, accompanied by an old plaque indicated that this was his house back in the day. I recalled that he was an astronomer – and a rather famous one. Then it came to me (okay I might have Googled his name on my phone) that this was the guy who discovered the seventh planet – Uranus (pronounced: ‘YOU run us’). It was time to find out more…

The museum tells his story well. You see, the world changed on 13 March 1781, when a musician looked up at the sky through a telescope of his own making. In one move he discovered a new planet and doubled the size of the known solar system. So, who was he?

Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel – as he was originally christened – was born in Hanover on the 15th November 1738 – the third son of a bandmaster in the Hanoverian Guards. He showed an early aptitude for music, mathematics and languages – with particular talents in violin and organ. By the time he was 14, he had joined his father as a musician in the Hanoverian Guards. During the Seven Years War, William and his brother Jacob made their way to London where they arrived in 1757. Finding London ‘overstocked with musicians’, they made their way further north.

Eventually William was appointed as organist at Halifax against stiff competition in 1764. Two years later he moved to Bath as organist for the Octagon Chapel, although the organ was not yet ready, so he was invited to play oboe in Linley’s Orchestra at the Pump Room (where excellent scones and tea can be enjoyed today to wonderful live chamber music).

At this time (1766) his interest in astronomy was sparked with an opportunity to look at Venus and a lunar eclipse through a hired telescope. But disatisfied with the quality of the optics, he set about making his own.

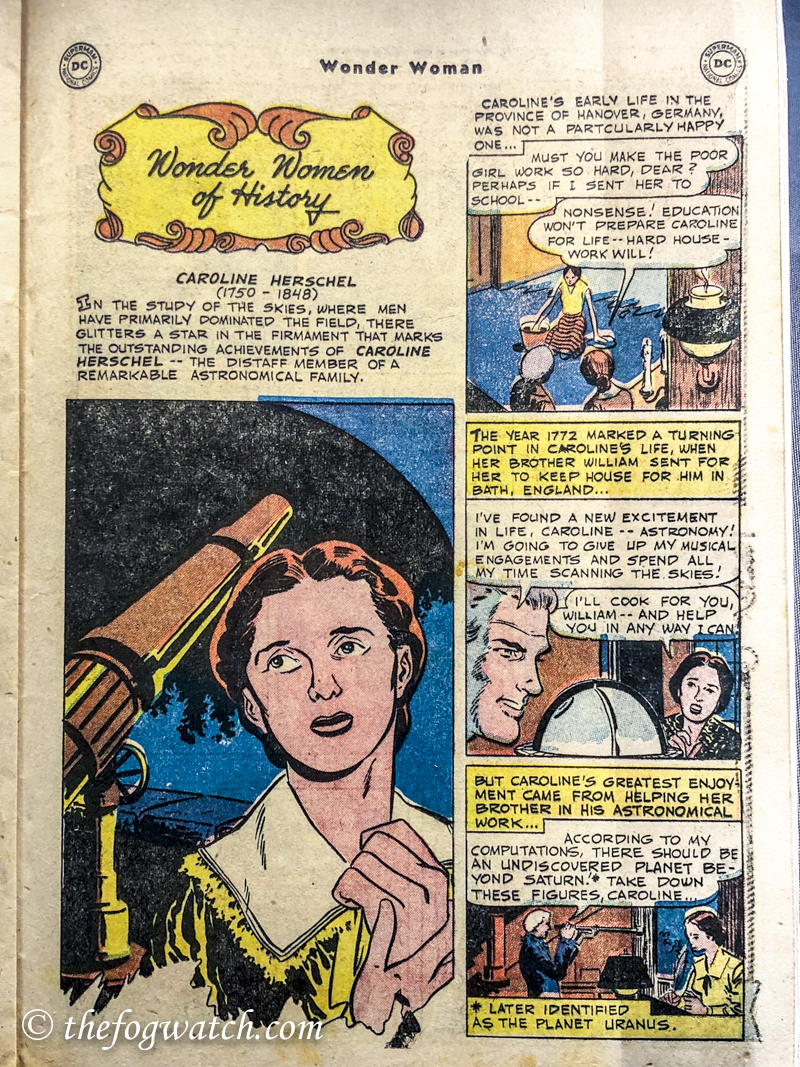

Visiting Hanover in 1772, William realised that his sister Caroline was being made to work as a household drudge, well below her musical and intellectual capacity. So he brought her back to England, to enable her to develop her career as a singer. William by this time was a Concert Director and there was every prospect of a bright musical career for them both. The story could have ended there, but William’s passion for astronomy took hold, and he began making his own ever larger telescopes. And he embarked on mapping the heavens, while his sister recorded his observations.

As his observations became ever more accurate, William was able to deduce the shape of the Milky Way and was trying to ascertain the distances of the stars. On 13 March 1781 he was examining stars in the Gemini constellation, when he noticed an object that could not be a star, as it was a definite disk, and over several observations, found that it moved against the starry background. He initially thought it to be a comet, so he wrote to the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, and to the Rev. T Hornsby, Radcliffe Observer at Oxford – and they quickly confirmed his discovery. Within days the orbit was calculated and soon announced that this was in fact, the discovery of a new planet. By May there was no doubt, with further confirmations from observers across continental Europe. By the end of the year, Herschel had been awarded the prestigious Copley Medal of the Royal Society, and he was elected to Fellow of the society.

Early in 1782, King George III (well prior to his illness) requested to meet William. So in May, he took his

This was ultimately the turning point, as William was offered a £200 per year pension and Caroline one of £50 per year as his assistant, on condition that they moved within easy reach of Windsor so that the King could visit and make observations through his telescopes. 7-foot enabled the Herschels to leave behind their music careers and focus full time on astronomy.

Ultimately moving to Observatory House in Slough, William was able to realise his grand project of constructing a 40-foot telescope

Caroline Herschel for her part, discovered eight new comets, 14 new nebulae and continued work on mapping the heavens. She was given several honours and was ultimately awarded the Gold Medal of the Astronomical Society. She was also made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society. Today, she is considered one of the great pioneering women in astronomy. Caroline Herschel died in 1848 at the age of 98 and is buried in her native Hanover.

The museum contains William’s workshop and a number of scientific instruments, as well as a small theatre room showing a biographical film of his life and that of his family.

Such an interesting and serendipitous discovery…always turn off the main road for an adventure 😉

Your posts are most enlightening. Thanks.

Thanks Ann

Wonderful and interesting, thank you, Jerry!

Thank you Anneliese – I found the museum to be a hidden gem 🙂

you should go to Greenwich Observatory, if you haven’t already – part of the large telescope is there as well as many other related objects –

best, Ala

Thanks Alan – Yes I’ve been to Greenwich Observatory – as you say, part of the 40-foot telescope is there, along with Harrison’s clocks for determining longitude – perhaps to be subject of a future post. The museum in Bath is a hidden gem, and often overlooked by visitors to Bath as it is overshadowed by the Roman baths.